Posts in Policies & Law

Page Content

Some thoughts on “cybersecurity” professionalization and education

[I was recently asked for some thoughts on the issues of professionalization and education of people working in cyber security. I realize I have been asked this many times, I and I keep repeating my answers, to various levels of specificity. So, here is an attempt to capture some of my thoughts so I can redirect future queries here.]

There are several issues relating to the area of personnel in this field that make issues of education and professional definition more complex and difficult to define. The field has changing requirements and increasing needs (largely because industry and government ignored the warnings some of us were sounding many years ago, but that is another story, oft told -- and ignored).

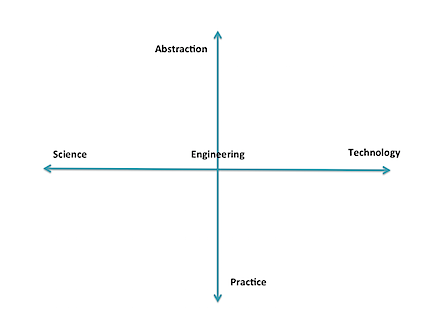

When I talk about educational and personnel needs, I discuss it metaphorically, using two dimensions. Along one axis is the continuum (with an arbitrary directionality) of science, engineering, and technology. Science is the study of fundamental properties and investigation of what is possible -- and the bounds on that possibility. Engineering is the study of design and building new artifacts under constraints. Technology is the study of how to choose from existing artifacts and employ them effectively to solve problems.

The second axis is the range of pure practice to abstraction. This axis is less linear than the other (which is not exactly linear, either), and I don't yet have a good scale for it. However, conceptually I relate it to applying levels of abstraction and anticipation. At its "practice" end are those who actually put in the settings and read the logs of currently-existing artifacts; they do almost no hypothesizing. Moving the other direction we see increasing interaction with abstract thought, people and systems, including operations, law enforcement, management, economics, politics, and eventually, pure theory. At one end, it is "hands-on" with the technology, and at the other is pure interaction with people and abstractions, and perhaps no contact with the technology.

There are also levels of mastery involved for different tasks, such as articulated in Bloom's Taxonomy of learning. Adding that in would provide more complexity than can fit in this blog entry (which is already too long).

The means of acquisition of necessary expertise varies for any position within this field. Many technicians can be effective with simple training, sometimes with at most on-the-job experience. They usually need little or no background beyond everyday practice. Those at the extremes of abstract thought in theory or policy need considerably more background, of the form we generally associate with higher education (although that is not strictly required), often with advanced degrees. And, of course, throughout, people need some innate abilities and motivation for the role they seek; Not everyone has ability, innate or developed, for each task area.

We have need of the full spectrum of these different forms of expertise, with government and industry currently putting an emphasis on the extremes of the quadrant involving technology/practice -- they have problems, now, and want people to populate the "digital ramparts" to defend them. This emphasis applies to those who operate the IDS and firewalls, but also to those who find ways to exploit existing systems (that is an area I believe has been overemphasized by government. Cf. my old blog post and a recent post by Gary McGraw). Many, if not most, of these people can acquire needed skills via training -- such as are acquired on the job, in 1-10 day "minicourses" provided by commercial organizations, and vocational education (e.g, some secondary ed, 2-year degree programs). These kinds of roles are easily designated with testing and course completion certificates.

Note carefully that there is no value statement being made here -- deeply technical roles are fundamental to civilization as we know it. The plumbers, electricians, EMTs, police, mechanics, clerks, and so on are key to our quality of life. The programs that prepare people for those careers are vital, too.

Of course, there are also careers that are directly located in many other places in the abstract plane illustrated above: scientists, software engineers, managers, policy makers, and even bow tie-wearing professors. :-)

One problem comes about when we try to impose sharply-defined categories on all of this, and say that person X has sufficient mastery of the category to perform tasks A, B, and C that are perceived as part of that category. However, those categories are necessarily shifting, not well-defined, and new needs are constantly arising. For instance, we have someone well trained in selecting and operating firewalls and IDS, but suddenly she is confronted with the need to investigate a possible act of nation-state espionage, determine what was done, and how it happened. Or, she is asked to set corporate policy for use of BYOD without knowledge of all the various job functions and people involved. Further deployment of mobile and embedded computing will add further shifts. The skills to do most of these tasks are not easily designated, although a combination of certificates and experience may be useful.

Too many (current) educational programs stress only the technology -- and many others include significant technology training components because of pressure by outside entities -- rather than a full spectrum of education and skills. We have a real shortage of people who have any significant insight into the scope of application of policy, management, law, economics, psychology and the like to cybersecurity, although arguably, those are some of the problems most obvious to those who have the long view. (BTW, that is why CERIAS was founded 15 years ago including faculty in nearly 20 academic departments: "cybersecurity" is not solely a technology issue; this has more recently been recognized by several other universities that are now also treating it holistically.) These other skill areas often require deeper education and repetition of exercises involving abstract thought. It seems that not as many people are naturally capable of mastering these skills. The primary means we use to designate mastery is through postsecondary degrees, although their exact meaning does vary based on the granting institution.

So, consider some the bottom line questions of "professionalization" -- what is, exactly, the profession? What purposes does it serve to delineate one or more niche areas, especially in a domain of knowledge and practice that changes so rapidly? Who should define those areas? Do we require some certification to practice in the field? Given the above, I would contend that too many people have too narrow a view of the domain, and they are seeking some way of ensuring competence only for their narrow application needs. There is therefore a risk that imposing "professional certifications" on this field would both serve to further skew the perception of what is involved, and discourage development of some needed expertise. Defining narrow paths or skill sets for "the profession" might well do the same. Furthermore, much of the body of knowledge is heuristics and "best practice" that has little basis in sound science and engineering. Calling someone in the 1600s a "medical professional" because he knew how to let blood, apply leeches, and hack off limbs with a carpenter's saw using assistants to hold down the unanesthitized patient creates a certain cognitive dissonance; today, calling someone a "cyber security professional" based on knowledge of how to configure Windows, deploy a firewall, and install anti-virus programs should probably be viewed as a similar oddity. We need to evolve to where the deployed base isn't so flawed, and we have some knowledge of what security really is -- evolve from the equivalent of "sawbones" to infectious disease specialists.

We have already seen some of this unfortunate side-effect with the DOD requirements for certifications. Now DOD is about to revisit the requirements, because they have found that many people with certifications don't have the skills they (DOD) think they want. Arguably, people who enter careers and seek (and receive) certification are professionals, at least in a current sense of that word. It is not their fault that the employers don't understand the profession and the nature of the field. Also notable are cases of people with extensive experience and education, who exceed the real needs, but are not eligible for employment because they have not paid for the courses and exams serving as gateways for particular certificates -- and cash cows for their issuing organizations. There are many disconnects in all of this. We also saw skew develop in the academic CAE program.

Here is a short parable that also has implications for this topic.

In the early 1900s, officials with the Bell company (telephones) were very concerned. They told officials and the public that there was a looming personnel crisis. They predicted that, at the then-current rate of growth, by the end of the century everyone in the country would need to be a telephone operator or telephone installer. Clearly, this was impossible.

Fast forward to recent times. Those early predictions were correct. Everyone was an installer -- each could buy a phone at the corner store, and plug it into a jack in the wall at home. Or, simpler yet, they could buy cellphones that were already on. And everyone was an operator -- instead of using plugboards and directory assistance, they would use an online service to get a phone number and enter it in the keypad (or speed dial from memory). What happened? Focused research, technology evolution, investment in infrastructure, economics, policy, and psychology (among others) interacted to "shift the paradigm" to one that no longer had the looming personnel problems.

If we devoted more resources and attention to the broadly focused issues of information protection (not "cyber" -- can we put that term to rest?), we might well obviate many of the problems that now require legions of technicians. Why do we have firewalls and IDS? In large part, because the underlying software and hardware was not designed for use in an open environment, and its development is terribly buggy and poorly configured. The languages, systems, protocols, and personnel involved in the current infrastructure all need rethinking and reengineering. But so long as the powers-that-be emphasize retaining (and expanding) legacy artifacts and compatibility based on up-front expense instead of overall quality, and in training yet more people to be the "cyber operators" defending those poor choices, we are not going to make the advances necessary to move beyond them (and, to repeat, many of us have been warning about that for decades). And we are never going to have enough "professionals" to keep them safe. We are focusing on the short term and will lose the overall struggle; we need to evolve our way out of the problems, not meet them with an ever-growing band of mercenaries.

The bottom line? We should be very cautious in defining what a "professional" is in this field so that we don't institutionalize limitations and bad practices. And we should do more to broaden the scope of education for those who work in those "professions" to ensure that their focus -- and skills -- are not so limited as to miss important features that should be part of what they do. As one glaring example, think "privacy" -- how many of the "professionals" working in the field have a good grounding and concern about preserving privacy (and other civil rights) in what they do? Where is privacy even mentioned in "cybersecurity"? What else are they missing?

[If this isn't enough of my musings on education, you can read two of my ideas in a white paper I wrote in 2010. Unfortunately, although many in policy circles say they like the ideas, no one has shown any signs of acting as a champion for either.]

[3/2/2013] While at the RSA Conference, I was interviewed by the Information Security Media Group on the topic of cyber workforce. The video is available online.

A Cautionary Incident

Recently, Amazon's cloud service failed for several customers, and has not come back fully for well over 24 hours. As of the time I write this, Amazon has not commented as to what caused the problem, why it took so long to fix, or how many customers it affected.

It seems a client of Amazon was not able to contact support, and posted in a support forum under the heading "Life of our patients is at stake - I am desperately asking you to contact." The body of the message was that "We are a monitoring company and are monitoring hundreds of cardiac patients at home. We were unable to see their ECG signals"

What ensued was a back-and-forth with others incredulous that such a service would not have a defined disaster plan and alternate servers defined, with the original poster trying to defend his/her position. At the end, as the Amazon service slowly came back, the original poster seemed to back off from the original claim, which implies either an attempt to evade further scolding (and investigation), or that the original posting was a huge exaggeration to get attention. Either way, the prospect of a mission critical system depending on the service was certainly disconcerting.

Personnel from Amazon apparently never contacted the original poster, despite that company having a Premium service contract.

25 or so years ago, Brian Reid defined a distributed system as "...one where I can't get my work done because a computer I never heard of is down." (Since then I've seen this attributed to Leslie Lamport, but at the time heard it attributed to Reid.) It appears that "The Cloud" is simply today's buzzword for a distributed system. There have been some changes to hardware and software, but the general idea is the same — with many of the limitations and cautions attendant thereto, plus some new ones unique to it. Those who extol its benefits (viz., cost) without understanding the many risks involved (security, privacy, continuity, legal, etc.) may find themselves someday making similar postings to support fora — as well as "position wanted" sites.

The full thread is available here.

A Recent Interview, and other info

I have not been blogging here for a while because of some health and workload issues. I hope to resume regular posts before too much longer.

Recently, I was interviewed about the current state of security . I think the interview came across fairly well, and captured a good cross-section of my current thinking on this topic. So, I'm posting a link to that interview here with some encouragement for you to go read it as a substitute for me writing a blog post:

Complexity Is Killing Us: A Security State of the Union With Eugene Spafford of CERIAS

Also, let me note that our annual CERIAS Symposium will be held April 5th & 6th here at Purdue. You can register and find more information via our web site.

But that isn't all!

- CERIAS news and events continue to be posted via the main CERIAS news feed

- Our security seminar series and podcasts continue on a weekly basis.

- The document archive continues to grow as our faculty and students continue to add new items to it.

Plus, all of the above are available via RSS feeds. We also have a Twitter feed: @cerias. Not all of our information goes out on the net, because some of it is restricted to our partner organizations, but eventually the majority of it makes it out to one of the above outlets.

So, although I haven't been blogging recently, there has still been a steady stream of activity from the 150+ people who make up the CERIAS "family."

What About the Other 11 Months?

October is "officially" National Cyber Security Awareness Month. Whoopee! As I write this, only about 27 more days before everyone slips back into their cyber stupor and ignores the issues for the other 11 months.

Yes, that is not the proper way to look at it. The proper way is to look at the lack of funding for long-term research, the lack of meaningful initiatives, the continuing lack of understanding that robust security requires actually committing resources, the lack of meaningful support for education, almost no efforts to support law enforcement, and all the elements of "Security Theater" (to use Bruce Schneier's very appropriate term) put forth as action, only to realize that not much is going to happen this month, either. After all, it is "Awareness Month" rather than "Action Month."

There was a big announcement at the end of last week where Secretary Napolitano of DHS announced that DHS had new authority to hire 1000 cybersecurity experts. Wow! That immediately went on my list of things to blog about, but before I could get to it, Bob Cringely wrote almost everything that I was going to write in his blog post The Cybersecurity Myth - Cringely on technology. (NB. Similar to Bob's correspondent, I have always disliked the term "cybersecurity" that was introduced about a dozen years ago, but it has been adopted by the hoi polloi akin to "hacker" and "virus.") I've testified before the Senate about the lack of significant education programs and the illusion of "excellence" promoted by DHS and NSA -- you can read those to get my bigger picture view of the issues on personnel in this realm. But, in summary, I think Mr. Cringely has it spot on.

Am I being too cynical? I don't really think so, although I am definitely seen by many as a professional curmudgeon in the field. This is the 6th annual Awareness Month and things are worse today than when this event was started. As one indicator, consider that the funding for meaningful education and research have hardly changed. NITRD (National Information Technology Research & Development) figures show that the fiscal 2009 allocation for Cyber Security and Information Assurance (their term) was about $321 million across all Federal agencies. Two-thirds of this amount is in budgets for Defense agencies, with the largest single amount to DARPA; the majority of these funds have gone to the "D" side of the equation (development) rather than fundamental research, and some portion has undoubtedly gone to support offensive technologies rather than building safer systems. This amount has perhaps doubled since 2001, although the level of crime and abuse has risen far more -- by at least two levels of magnitude. The funding being made available is a pittance and not enough to really address the problems.

Here's another indicator. A recent conversation with someone at McAfee revealed that new pieces of deployed malware are being indexed at a rate of about 10 per second -- and those are only the ones detected and being reported! Some of the newer attacks are incredibly sophisticated, defeating two-factor authentication and falsifying bank statements in real time. The criminals are even operating a vast network of fake merchant sites designed to corrupt visitors' machines and steal financial information. Some accounts place the annual losses in the US alone at over $100 billion per year from cyber crime activities -- well over 300 times everything being spent by the US government in R&D to stop it. (Hey, but what's 100 billion dollars, anyhow?) I have heard unpublished reports that some of the criminal gangs involved are spending tens of millions of dollars a year to write new and more effective attacks. Thus, by some estimates, the criminals are vastly outspending the US Government on R&D in this arena, and that doesn't count what other governments are spending to steal classified data and compromise infrastructure. They must be investing wisely, too: how many instances of arrests and takedowns can you recall hearing about recently?

Meanwhile, we are still awaiting the appointment of the National Cyber Cheerleader. For those keeping score, the President announced that the position was critical and he would appoint someone to that position right away. That was on May 29th. Given the delay, one wonders why the National Review was mandated as being completed in a rush 60 day period. As I noted in that earlier posting, an appointment is unlikely to make much of a difference as the position won't have real authority. Even with an appointment, there is disagreement about where the lead for cyber should be, DHS or the military. Neither really seems to take into account that this is at least as much a law enforcement problem as it is one of building better defenses. The lack of agreement means that the tenure of any appointment is likely to be controversial and contentious at worst, and largely ineffectual at best.

I could go on, but it is all rather bleak, especially when viewed through the lens of my 20+ years experience in the field. The facts and trends have been well documented for most of that time, too, so it isn't as if this is a new development. There are some bright points, but unless the problem gets a lot more attention (and resources) than it is getting now, the future is not going to look any better.

So, here are my take-aways for National Cyber Security Awareness:

- the government is more focused on us being "aware" than "secure"

- the criminals are probably outspending the government in R&D

- no one is really in charge of organizing the response, and there isn't agreement about who should

- there aren't enough real experts, and there is little real effort to create more

- too many people think "certification" means "expertise"

- law enforcement in cyber is not a priority

- real education is not a real priority

But hey, don't give up on October! It's also Vegetarian Awareness Month, National Liver Awareness Month, National Chiropractic Month, and Auto Battery Safety Month (among others). Undoubtedly there is something to celebrate without having to wait until Halloween. And that's my contribution for National Positive Attitude Month.

Still no sign of land

I am a big fan of the Monty Python troupe. Their silly take on several topics helped point out the absurd and pompous, and still do, but sometimes were simply lunatic in their own right.

One of their sketches, about a group of sailors stuck in a lifeboat came to mind as I was thinking about this post. The sketch starts (several times) with the line "Still no sign of land." The sketch then proceeds to a discussion of how they are so desperate that they may have to resort to cannibalism.

So why did that come to mind?

We still do not have a national Cyber Cheerleader in the Executive Office of the President. On May 29th, the President announced that he would appoint one – that cyber security was a national priority.

Three months later – nada.

Admittedly, there are other things going on: health care reform, a worsening insurgency problem in Afghanistan, hesitancy in the economic recovery, and yet more things going on that require attention from the White House. Still, cyber continues to be a problem area with huge issues. See some of the recent news to see that there is no shortage of problems – identity theft, cyber war questions, critical infrastructure vulnerability, supply chain issues, and more.

Rumor has it that several people have been approached for the Cheerleader position, but all have turned it down. This isn't overly surprising – the position has been set up as basically one where blame can be placed when something goes wrong rather than as a position to support real change. There is no budget authority, seniority, or leverage over Federal agencies where the problems occur, so there is no surprise that it is not wanted. Anyone qualified for a high-level position in this area should recognize what I described 20 years ago in "Spaf's First Law":

If you have responsibility for security but have no authority to set rules or punish violators, your own role in the organization is to take the blame when something big goes wrong.

I wonder how many false starts it will take before it is noticed that there is something wrong with the position if good people don't want it? And will that be enough to result in a change in the way the position is structured?

Meanwhile, we are losing good people from what senior leadership exists. Melissa Hathaway has resigned from the temporary position at the NSC from which she led the 60-day study, and Mischel Kwon has stepped down from leadership of US-CERT. Both were huge assets to the government and the public, and we have all lost as a result of their departure.

The crew of the lifeboat is dwindling. Gee, what next? Well, funny you should mention that.

Last week, I attended the "Cyber Leap Year Summit," which I have variously described to people who have asked as "An interesting chance to network" to "Two clowns short of a circus." (NB. I was there, so it was not three clowns short.)

The implied premise of the Summit, that bringing together a group of disparate academics and practitioners can somehow lead to a breakthrough is not a bad idea in itself. However, when you bring together far too many of them under a facilitation protocol that most of them have not heard of coupled with a forced schedule, it shouldn't be a surprise if the result in much other than some frustration. At least, that is what I heard from most of the participants I spoke with. It remains to be seen if the reporters from the various sections are able to glean something useful from the ideas that were so briefly discussed. (Trying to winnow "the best" idea from 40 suggestions given only 75 minutes and 40 type A personalities is not a fun time.)

There was also the question of "best" being brought together. In my session, there were people present who had no idea about basic security topics or history. Some of us made mention of well-known results or systems, and they went completely over the heads of the people present. Sometimes, they would point this out, and we lost time explaining. As the session progressed, the parties involved seemed to simply assume that if they hadn't heard about it, it couldn't be important, so they ignored the comments.

Here are three absurdities that seem particularly prominent to me about the whole event:

- Using "game change" as the fundamental theme is counter-productive to the issue. Referring to cyber security and privacy protection as a "game" trivializes it, and if nothing substantial occurs, it suggests that we simply haven't won the "game" yet. But in truth, these problems are something fundamental to the functioning of society, the economy, national defense, and even the rule of law. We cannot afford to "not win" this. We should not trivialize it by calling it a "game."

- Putting an arbitrary 60-90 day timeline on the proposed solutions exacerbates the problems. There was no interest in discussing the spectrum of solutions, but only talking about things that could be done right away. Unfortunately, this tends to result in people talking about more patches rather than looking at fundamental issues. It also means that potential solutions that require time (such as phasing in some product liability for bad software) are outside the scope of both discussion and consideration, and this continues to perpetuate the idea that quick fixes are somehow the solution.

- Suggesting that all that is needed is for the government to sponsor some group-think, feel-good meeting to come up with solutions is inane. Some of us have been looking at the problem set for decades, and we know some of what is needed. It will take sustained effort and some sacrifice to make a difference. Other parts of the problem are going to require sustained investigation and data gathering. There is no political will for either. Some of the approaches were even brought up in our sessions; in the one I was in, which had many economists and people from industry, the ideas were basically voted down (or derided, contrary to the protocol of the meeting) and dropped. This is part of the issue: the parties most responsible for the problem do not want to bear any responsibility for the fixes.

I raised the first two issues as the first comments in the public Q&A session on Day 1. Aneesh Chopra, the Federal Chief Technology Officer (CTO), and Susan Alexander, the Chief Technology Officer for Information and Identity Assurance at DoD, were on the panel to which I addressed the questions. I was basically told not to ask those kinds of questions, and to sit down. although the response was phrased somewhat less forcefully than that. Afterwards, no less than 22 people told me that they wanted to ask the same questions (I started counting after #5). Clearly, I was not alone in questioning the formulation of the meeting.

Do I seem discouraged? A bit. I had hoped that we would see a little more careful thought involved. There were many government observers present, and in private, one-on-one discussions with them, it was clear they were equally discouraged with what they were hearing, although they couldn't state that publicly.

However, this is yet another in long line of meetings and reports with which I have had involvement, where the good results are ignored, and the "captains of industry and government" have focused on the wrong things. But by holding continuing workshops like this one, at least it appears that the government is doing something. If nothing comes of it, they can blame the participants in some way for not coming up with good enough ideas rather than take responsibility for not asking the right questions or being willing to accept answers that are difficult to execute.

Too cynical? Perhaps. But I will continue to participate because this is NOT a "game," and the consequences of continuing to fail are not something we want to face — even with "...white wine sauce with shallots, mushrooms and garlic."