Posts in Infosec Education

Page Content

Some thoughts on “cybersecurity” professionalization and education

[I was recently asked for some thoughts on the issues of professionalization and education of people working in cyber security. I realize I have been asked this many times, I and I keep repeating my answers, to various levels of specificity. So, here is an attempt to capture some of my thoughts so I can redirect future queries here.]

There are several issues relating to the area of personnel in this field that make issues of education and professional definition more complex and difficult to define. The field has changing requirements and increasing needs (largely because industry and government ignored the warnings some of us were sounding many years ago, but that is another story, oft told -- and ignored).

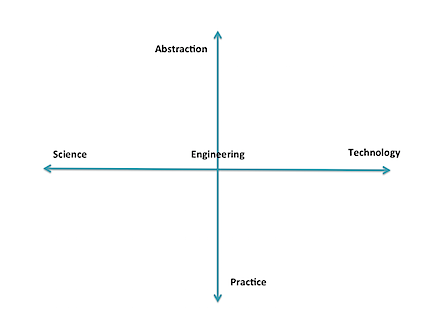

When I talk about educational and personnel needs, I discuss it metaphorically, using two dimensions. Along one axis is the continuum (with an arbitrary directionality) of science, engineering, and technology. Science is the study of fundamental properties and investigation of what is possible -- and the bounds on that possibility. Engineering is the study of design and building new artifacts under constraints. Technology is the study of how to choose from existing artifacts and employ them effectively to solve problems.

The second axis is the range of pure practice to abstraction. This axis is less linear than the other (which is not exactly linear, either), and I don't yet have a good scale for it. However, conceptually I relate it to applying levels of abstraction and anticipation. At its "practice" end are those who actually put in the settings and read the logs of currently-existing artifacts; they do almost no hypothesizing. Moving the other direction we see increasing interaction with abstract thought, people and systems, including operations, law enforcement, management, economics, politics, and eventually, pure theory. At one end, it is "hands-on" with the technology, and at the other is pure interaction with people and abstractions, and perhaps no contact with the technology.

There are also levels of mastery involved for different tasks, such as articulated in Bloom's Taxonomy of learning. Adding that in would provide more complexity than can fit in this blog entry (which is already too long).

The means of acquisition of necessary expertise varies for any position within this field. Many technicians can be effective with simple training, sometimes with at most on-the-job experience. They usually need little or no background beyond everyday practice. Those at the extremes of abstract thought in theory or policy need considerably more background, of the form we generally associate with higher education (although that is not strictly required), often with advanced degrees. And, of course, throughout, people need some innate abilities and motivation for the role they seek; Not everyone has ability, innate or developed, for each task area.

We have need of the full spectrum of these different forms of expertise, with government and industry currently putting an emphasis on the extremes of the quadrant involving technology/practice -- they have problems, now, and want people to populate the "digital ramparts" to defend them. This emphasis applies to those who operate the IDS and firewalls, but also to those who find ways to exploit existing systems (that is an area I believe has been overemphasized by government. Cf. my old blog post and a recent post by Gary McGraw). Many, if not most, of these people can acquire needed skills via training -- such as are acquired on the job, in 1-10 day "minicourses" provided by commercial organizations, and vocational education (e.g, some secondary ed, 2-year degree programs). These kinds of roles are easily designated with testing and course completion certificates.

Note carefully that there is no value statement being made here -- deeply technical roles are fundamental to civilization as we know it. The plumbers, electricians, EMTs, police, mechanics, clerks, and so on are key to our quality of life. The programs that prepare people for those careers are vital, too.

Of course, there are also careers that are directly located in many other places in the abstract plane illustrated above: scientists, software engineers, managers, policy makers, and even bow tie-wearing professors. :-)

One problem comes about when we try to impose sharply-defined categories on all of this, and say that person X has sufficient mastery of the category to perform tasks A, B, and C that are perceived as part of that category. However, those categories are necessarily shifting, not well-defined, and new needs are constantly arising. For instance, we have someone well trained in selecting and operating firewalls and IDS, but suddenly she is confronted with the need to investigate a possible act of nation-state espionage, determine what was done, and how it happened. Or, she is asked to set corporate policy for use of BYOD without knowledge of all the various job functions and people involved. Further deployment of mobile and embedded computing will add further shifts. The skills to do most of these tasks are not easily designated, although a combination of certificates and experience may be useful.

Too many (current) educational programs stress only the technology -- and many others include significant technology training components because of pressure by outside entities -- rather than a full spectrum of education and skills. We have a real shortage of people who have any significant insight into the scope of application of policy, management, law, economics, psychology and the like to cybersecurity, although arguably, those are some of the problems most obvious to those who have the long view. (BTW, that is why CERIAS was founded 15 years ago including faculty in nearly 20 academic departments: "cybersecurity" is not solely a technology issue; this has more recently been recognized by several other universities that are now also treating it holistically.) These other skill areas often require deeper education and repetition of exercises involving abstract thought. It seems that not as many people are naturally capable of mastering these skills. The primary means we use to designate mastery is through postsecondary degrees, although their exact meaning does vary based on the granting institution.

So, consider some the bottom line questions of "professionalization" -- what is, exactly, the profession? What purposes does it serve to delineate one or more niche areas, especially in a domain of knowledge and practice that changes so rapidly? Who should define those areas? Do we require some certification to practice in the field? Given the above, I would contend that too many people have too narrow a view of the domain, and they are seeking some way of ensuring competence only for their narrow application needs. There is therefore a risk that imposing "professional certifications" on this field would both serve to further skew the perception of what is involved, and discourage development of some needed expertise. Defining narrow paths or skill sets for "the profession" might well do the same. Furthermore, much of the body of knowledge is heuristics and "best practice" that has little basis in sound science and engineering. Calling someone in the 1600s a "medical professional" because he knew how to let blood, apply leeches, and hack off limbs with a carpenter's saw using assistants to hold down the unanesthitized patient creates a certain cognitive dissonance; today, calling someone a "cyber security professional" based on knowledge of how to configure Windows, deploy a firewall, and install anti-virus programs should probably be viewed as a similar oddity. We need to evolve to where the deployed base isn't so flawed, and we have some knowledge of what security really is -- evolve from the equivalent of "sawbones" to infectious disease specialists.

We have already seen some of this unfortunate side-effect with the DOD requirements for certifications. Now DOD is about to revisit the requirements, because they have found that many people with certifications don't have the skills they (DOD) think they want. Arguably, people who enter careers and seek (and receive) certification are professionals, at least in a current sense of that word. It is not their fault that the employers don't understand the profession and the nature of the field. Also notable are cases of people with extensive experience and education, who exceed the real needs, but are not eligible for employment because they have not paid for the courses and exams serving as gateways for particular certificates -- and cash cows for their issuing organizations. There are many disconnects in all of this. We also saw skew develop in the academic CAE program.

Here is a short parable that also has implications for this topic.

In the early 1900s, officials with the Bell company (telephones) were very concerned. They told officials and the public that there was a looming personnel crisis. They predicted that, at the then-current rate of growth, by the end of the century everyone in the country would need to be a telephone operator or telephone installer. Clearly, this was impossible.

Fast forward to recent times. Those early predictions were correct. Everyone was an installer -- each could buy a phone at the corner store, and plug it into a jack in the wall at home. Or, simpler yet, they could buy cellphones that were already on. And everyone was an operator -- instead of using plugboards and directory assistance, they would use an online service to get a phone number and enter it in the keypad (or speed dial from memory). What happened? Focused research, technology evolution, investment in infrastructure, economics, policy, and psychology (among others) interacted to "shift the paradigm" to one that no longer had the looming personnel problems.

If we devoted more resources and attention to the broadly focused issues of information protection (not "cyber" -- can we put that term to rest?), we might well obviate many of the problems that now require legions of technicians. Why do we have firewalls and IDS? In large part, because the underlying software and hardware was not designed for use in an open environment, and its development is terribly buggy and poorly configured. The languages, systems, protocols, and personnel involved in the current infrastructure all need rethinking and reengineering. But so long as the powers-that-be emphasize retaining (and expanding) legacy artifacts and compatibility based on up-front expense instead of overall quality, and in training yet more people to be the "cyber operators" defending those poor choices, we are not going to make the advances necessary to move beyond them (and, to repeat, many of us have been warning about that for decades). And we are never going to have enough "professionals" to keep them safe. We are focusing on the short term and will lose the overall struggle; we need to evolve our way out of the problems, not meet them with an ever-growing band of mercenaries.

The bottom line? We should be very cautious in defining what a "professional" is in this field so that we don't institutionalize limitations and bad practices. And we should do more to broaden the scope of education for those who work in those "professions" to ensure that their focus -- and skills -- are not so limited as to miss important features that should be part of what they do. As one glaring example, think "privacy" -- how many of the "professionals" working in the field have a good grounding and concern about preserving privacy (and other civil rights) in what they do? Where is privacy even mentioned in "cybersecurity"? What else are they missing?

[If this isn't enough of my musings on education, you can read two of my ideas in a white paper I wrote in 2010. Unfortunately, although many in policy circles say they like the ideas, no one has shown any signs of acting as a champion for either.]

[3/2/2013] While at the RSA Conference, I was interviewed by the Information Security Media Group on the topic of cyber workforce. The video is available online.

Centers of ... Adequacy, Revisited

Almost two years ago I wrote in this blog about how CERIAS (and Purdue) was not going to resubmit for the NSA/DHS Centers of Academic Excellence program.

Some of you may notice that Purdue is listed among this year's (2010) group of educational institutions receiving designation as one of the CAEs in that program. Specifically, we have received designation as a CAE-R (Center of Academic Excellence in Research).

"What changed?" you may ask, and "Why did you submit?"

The simple answers are "Not that much," and "Because it was the least-effort solution to a problem." A little more elaborate answers follow. (It would help if you read the previous post on this topic to put what follows in context.)

Basically, the first three reasons I listed in the previous post still hold:

- The CAE program is still not a good indicator of real excellence. The program now has 125 designated institutions, ranging from top research universities in IA (e.g., Purdue, CMU, Georgia Tech) to 2-year community colleges. To call all of those programs "excellent" and to suggest they are equivalent in a meaningful way is unfair to students who wish to enter the field, and unfair to the people who work at all of those institutions. I have no objection to labeling the evaluation as a high-level evaluation of competence, but "excellence" is still not appropriate.

- The CNSS standards are still used for the CAE and are not really appropriate for the field as it currently stands. Furthermore, the IACE program used to certify CNSS compliance explicitly notes "The certification process does not address the quality of the presentation of the material within the courseware; it simply ensures that all the elements of a specific standard are included.." How the heck can a program be certified as "excellent" when the quality is not addressed? By that measure, a glass of water is insufficient, but drowning someone under 30ft of water is "excellent."

- There still are no dedicated resources for CAE schools. There are several grant programs and scholarships via NSF, DHS, and DOD for which CAE programs are eligible, but most of those don't actually require CAE status, nor does CAE status provide special consideration.

What has changed is the level of effort to apply or renew at least the CAE-R stamp. The designation is now good for 5 academic years, and that is progress. Also, the requirements for the CAE-R designation were easily satisfied by a few people in a matter of several hours mining existing literature and research reports. Both of those were huge pluses for us in submitting the application and reducing the overhead to a more acceptable level given the return on investment.

The real value in this, and the reason we entered into the process is that a few funding opportunities have indicated that applicants' institutions must be certified as a CAE member or else the applicant must document a long list of items to show "equivalence." As our faculty and staff compete for some of these grants, the cost-benefit tradeoff suggested that a small group to go through the process once, for the CAE-R. Of course, this raises the question of why the funding agencies suggest that XX Community College is automatically qualified to submit a grant, while a major university that is not CAE certified (MIT is an example) has to prove that it is qualified!

So, for us, it came down to a matter of deciding whether to stay out of the program as a matter of principle or submit an application to make life a little simpler for all of our faculty and staff when submitting proposals. In the end, several of our faculty & the staff decided to do it over an afternoon because they wanted to make their own proposals simpler to produce. And, our attempt to galvanize some movement away from the CAE program produced huge waves of ...apathy... by other schools; they appear to have no qualms about standing in line for government cheese. Thus, with somewhat mixed feelings by some of us, we got our own block of curd, with an expiration date of 2015.

Let me make very clear -- we are very supportive of any faculty willing to put in the time to develop a program and working to educate students to enter this field. We are also very glad that there are people in government who are committed to supporting that academic effort. We are in no way trying to denigrate any institution or individual involved in the CAE program. But the concept of giving a gold star to make everyone feel good about doing what should be the minimum isn't how we should be teaching, or about how we should be promoting good cybersecurity education.

(And I should also add that not every faculty member here holds the opinions expressed above.)

Own Your Own Space

I have been friends with Linda McCarthy for many years. As a security strategist she has occupied a number of roles -- running research groups, managing corporate security, writing professional books, serving as a senior consultant, conducting professional training....and more. That she isn't widely known is more a function of her not seeking it by having a blog or gaining publicity by publishing derivative hacks to software than it is anything else; There are many in the field who are highly competent and who practice out of the spotlight most of the time.

One of Linda's passions over the last few years has been in reaching out to kids -- especially teens -- to make them aware of how to be safe when online. Her most recent effort is an update to her book for the youngest computer users. The book is now published under the Creative Commons license. The terms allow free use of the book for personal use. That's a great deal for a valuable resource!

I'm enclosing the recent press release on the book to provide all the information on how to get the book (or selected chapters).

If you're an experienced computer user, this will all seem fairly basic. But that's the point -- the basics require special care to present to new users, and in terms they understand. (And yes, this is targeted mostly to residents of the U.S.A. and maybe Canada, but the material should be useful for everyone, including parents.)

Industry-Leading Internet Security Book for Kids, Teens, Adults Available Now as Free Download

Own Your Space® teams with Teens, Experts, Corporate Sponsors for Kids' Online Safety

SAN FRANCISCO, June 17 -- As unstructured summertime looms, kids and teens across the nation are likely to be spending more time on the Internet and texting.

Now, a free download is available to help them keep themselves safer both online and while using a cell phone.

Own Your Space®, the industry-leading Internet security book for youth, parents, and adults, was first written by Linda McCarthy, a 20-year network and Internet-security expert.

This all-new free edition -- by McCarthy, security pros, and dedicated teenagers -- teaches youths and even their parents how to keep themselves "and their stuff" safer online.

A collaboration between network-security experts, teenagers, and artists, the flexible licensing of Creative Commons, and industry-leading corporate sponsors, together have made it possible for everyone on the Internet to access Own Your Space for free via myspace.com/ownyourspace, facebook.com/ownyourspace.net, and www.ownyourspace.net.

"With the rise of high-technology communications within the teen population, this is the obvious solution to an increasingly ubiquitous problem: how to deliver solid, easy-to-understand Internet security information into their hands? By putting it on the Internet and their hard drives, for free," said Linda McCarthy, former Senior Director of Internet Safety at Symantec.

Besides the contributors' own industry experience, Own Your Space also boasts the "street cred" important to the book's target audience; this new edition has been overseen by a cadre of teens who range in age from 13 to 17.

"In this age of unsafe-Internet and risky-texting practices that have led to the deaths and the jailing of minors, I'm thankful for everyone who works toward and sponsors our advocacy to keep more youth safe while online and on cell phones," McCarthy said.

Everyone interested in downloading Own Your Space® for free can visit myspace.com/ownyourspace, facebook.com/ownyourspace.net, and www.ownyourspace.net. Corporations who would like to increase the availability of the book and promote child safety online through their hardware and Web properties can contact Linda McCarthy atlmccarthy@ownyourspace.net.

McCarthy is releasing the book in June to celebrate Internet Safety Month.

Having an Impact on Cybersecurity Education

The 12th anniversary of CERIAS is looming (in May). As part of the display materials for our fast-approaching annual CERIAS Symposium (register now!), I wanted to get a sense of the impact of our educational activities in addition to our research. What I found surprised me -- and may surprise many others!

Strategic Planning

Back in 1997, a year before the formation of CERIAS, I presented testimony before a U.S. House of Representatives hearing on "Secure Communications." For that presentation, I surveyed peers around the country to determine something about the capacity of U.S. higher education in the field of information security and privacy (this was before the term "cyber" was popularized). I discovered that, at the time, there were only four defined programs in the country. We estimated that there were fewer than 20 academic faculty in the US at that time who viewed information security other than cryptography as their primary area of emphasis. (The reason we excluded cryptography was because there were many people who were working in abstract mathematics that could be applied to cryptography but who knew extremely little about information security as a field, and certainly were not teaching it).

The best numbers I could come up with from surveying all those people was that, as of 1997, U.S. higher education was graduating only about three new Ph.D. students a year in information security, Thus, there were also very few faculty producing new well-educated experts at any level, and too small a population to easily grow new programs. I noted in my remarks that the output was too low by at least two orders of magnitude for national needs (and was at least 3-5 orders too low for international needs).

As I have noted before, my testimony helped influence the creations of (among other things) the NSA's CAE program and the Scholarship for Service program. Both provided some indirect support for increasing the number of Ph.D graduates and courses at all postsecondary levels. The SfS has been a qualified success, although the CAE program not so much.

When CERIAS was formed, one element of our strategic plan was to focus on helping other institutions build up their capacity to offer infosec courses at every level, as a matter of strategic leadership. We decided to do this through five concurrent approaches:

- Create new classes at every level at Purdue, across several departments

- Find ways to get more Ph.D.s through our program, and help place them at other academic institutions

- Host visitors and postdocs, provide them with additional background in the field for eventual use at other academic institutions

- Create an affiliates program with other universities and colleges to exchange educational materials, speakers, best practices, and more

- Create opportunities for enrichment programs for faculty at other schools, such as a summer certificate program for educators at 2 and 4-year colleges.

Our goal was not only to produce new expertise, but to retrain personnel with strong backgrounds in computing and computing education. Transformation was the only way we could see that a big impact could be made quickly.

Outcome

We have had considerable success at all five of these initiatives. Currently, there are several dozen classes in CERIAS focus areas across Purdue. In addition to the more traditional graduate degrees, our Interdisciplinary graduate degree program is small but competitive and has led to new courses. Overall, on the Ph.D. front, we anticipate another 15 Ph.D. grads this May, bringing the total CERIAS output of PhD.s over 12 years to 135. To the best of our ability to estimate (using some figures from NSF and elsewhere), that was about 25% of all U.S. PhDs in the first decade that CERIAS was in existence, and we are currently graduating about 20% of U.S. output. Many of those graduates have taught or still teach at colleges and universities, even if part-time. We have also graduated many hundreds of MS and undergrad students with some deep coursework and research experience in information security and privacy issues.

We have hosted several score post-docs and visiting faculty over the years, and always welcome more --- our only limitation right now is available funding. For several years, we had an intensive summer program for faculty from 2 and 4-year schools, many of which are serving minority and disadvantaged populations. Graduates of that program went on to create many new courses at their home institutions. We had to discontinue this program after a few years because of, again, lack of funding.

Our academic affiliates program ran for five years, and we believe it was a great success. Several schools with only one or two faculty working in the area were able to leverage the partnership to get grants and educational resources, and are now notable for their own intrinsic capabilities. We discontinued the affiliates program several years ago as we realized all but one of those partners had "graduated."

So, how can we measure the impact of this aspect of our strategic plan? Perhaps by simply coming up with some numbers....We compiled a list of anyone who had been through CERIAS (and a few years of COAST, prior) who:

- Got a PhD from within Purdue and was part of CERIAS

- Did a postdoc with CERIAS to learn (more) about cybersecurity/privacy

- Came as a visiting faculty member to learn (more) about cybersecurity/privacy

- Participated in one of our summer institutes for faculty

We gathered from them (as many as we could reach) the names of any higher education institution where they taught courses related to security, privacy or cyber crime. We also folded in the names of our academic affiliates at which such courses were (or still are) offered. The resultant list has over 100 entries! Even if we make a somewhat moderate estimate of the number of people who took these classes, we are well into the tens of thousands of students impacted, in some way, and possibly above 100,000, worldwide. That doesn't include the indirect effect, because many of those students have gone on (or will) to teach in higher education -- some of our Ph.D. grads have already turned out Ph.D. grads who now have their own Ph.D. students!

Seeing the scope of that impact is gratifying. And knowing that we will do more in the years ahead is great motivation, too.

Of course, it is also a little frustrating, because we could have done more, and more needs to be done. However, the approaches we have used (and are interested in trying next) never fit into any agency BAA. Thus, we have (almost) never been able to get grant support for our educational efforts. And, in many cases, the effort, overhead and delays in the application processes aren't worth the funding that is available. (The same is true of many of our research and outreach activities, but that is a topic for another time.)

We've been able to get this far because of the generosity of the companies and agencies that have been CERIAS general supporters over the years -- thank you! Our current supporters are listed on the CERIAS WWW site (hint: we're open to adding more!). We're also had a great deal of support within Purdue University from faculty, staff and the administration. It has been a group effort, but one that has really made a positive difference in the world....and provides us motivation to continue to greater heights.

See you at the CERIAS Symposium!

Institutions

Here is the list of the 106 107 108 educational institutions [last updated 3/21,1600 EDT]:

- Air Force Institute of Technology

- Amrita Vishwa Vidyapeetham, Coimbatore, India

- Brigham Young University

- Cairo University (Egypt)

- California State University Sacramento

- California State University Long Beach

- Carnegie Mellon University

- Case Western Reserve University

- Charleston Southern University

- Chunggnam National University, Korea

- College of Aeronautical Engineering, PAF Academy, Risalpur Pakistan

- College of Saint Elizabeth

- Colorado State University

- East Tennessee State University

- Eastern Michigan University

- Felician College

- George Mason University

- Georgia Institute of Technology

- Georgia Southern University

- Georgetown University

- Hannam University, Korea

- Helsinki University of Technology (Finland)

- Hong Kong University of Science & Technology

- Illinois Wesleyan University

- Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore

- Indiana University-Purdue University, Fort Wayne

- Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis

- International University, Bruchsal, Germany

- Iowa State University

- James Madison University

- John Marshall School of Law

- KAIST (Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology)

- Kansas State University

- Kennesaw State University

- Kent State University

- Korea University

- Kyungpook National University, Korea

- Linköpings Universitet, Linköping Sweden

- Marquette University

- Miami University of Ohio

- Missouri Univ S&T

- Murray State University

- Myongji University, Korea

- N. Georgia College & State Univ.

- National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan

- National Taiwan University

- National University of Singapore

- New Jersey Institute of Technology

- North Carolina State University

- Norwalk Community College

- Oberlin College

- Penn State University

- Purdue University Calumet

- Purdue University West Lafayette

- Qatar University, Qatar

- Queensland Institute of Technology, Australia

- Radford University

- Rutgers University

- Sabanci University, Turkey

- San José State University

- Shoreline Community College

- Simon Fraser University

- Southwest Normal University (China)

- Southwest Texas Junior College

- SUNY Oswego

- SUNY Stony Brook

- Syracuse University

- Technische Universität München (TU-Munich)

- Texas A & M Univ. Corpus Christi

- Texas A & M Univ. Commerce

- Tuskegee University

- United States Military Academy

- Universidad Católica Boliviana San Pablo, Bolivia

- Universität Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

- University of Albany

- University of Calgary

- University of California, Berkeley

- University of Cincinnati

- University of Connecticut

- University of Dayton

- University of Denver

- University of Florida

- University of Kansas

- University of Louisville

- University of Maine at Fort Kent

- University of Maryland University College

- University of Mauritius, Mauritius

- University of Memphis

- University of Milan, Italy

- University of Minnesota

- University of Mississippi

- University of New Haven (CT)

- University of New Mexico

- University of North Carolina, Charlotte

- University of Notre Dame

- University of Ohio

- University of Pittsburgh

- University of Texas, Dallas

- University of Texas, San Antonio

- University of Trento (Italy)

- University of Virginia

- University of Washington

- University of Waterloo

- University of Zurich

- Virginia Tech

- Washburn University

- Western Michigan University

- Zayed University, UAE

What About the Other 11 Months?

October is "officially" National Cyber Security Awareness Month. Whoopee! As I write this, only about 27 more days before everyone slips back into their cyber stupor and ignores the issues for the other 11 months.

Yes, that is not the proper way to look at it. The proper way is to look at the lack of funding for long-term research, the lack of meaningful initiatives, the continuing lack of understanding that robust security requires actually committing resources, the lack of meaningful support for education, almost no efforts to support law enforcement, and all the elements of "Security Theater" (to use Bruce Schneier's very appropriate term) put forth as action, only to realize that not much is going to happen this month, either. After all, it is "Awareness Month" rather than "Action Month."

There was a big announcement at the end of last week where Secretary Napolitano of DHS announced that DHS had new authority to hire 1000 cybersecurity experts. Wow! That immediately went on my list of things to blog about, but before I could get to it, Bob Cringely wrote almost everything that I was going to write in his blog post The Cybersecurity Myth - Cringely on technology. (NB. Similar to Bob's correspondent, I have always disliked the term "cybersecurity" that was introduced about a dozen years ago, but it has been adopted by the hoi polloi akin to "hacker" and "virus.") I've testified before the Senate about the lack of significant education programs and the illusion of "excellence" promoted by DHS and NSA -- you can read those to get my bigger picture view of the issues on personnel in this realm. But, in summary, I think Mr. Cringely has it spot on.

Am I being too cynical? I don't really think so, although I am definitely seen by many as a professional curmudgeon in the field. This is the 6th annual Awareness Month and things are worse today than when this event was started. As one indicator, consider that the funding for meaningful education and research have hardly changed. NITRD (National Information Technology Research & Development) figures show that the fiscal 2009 allocation for Cyber Security and Information Assurance (their term) was about $321 million across all Federal agencies. Two-thirds of this amount is in budgets for Defense agencies, with the largest single amount to DARPA; the majority of these funds have gone to the "D" side of the equation (development) rather than fundamental research, and some portion has undoubtedly gone to support offensive technologies rather than building safer systems. This amount has perhaps doubled since 2001, although the level of crime and abuse has risen far more -- by at least two levels of magnitude. The funding being made available is a pittance and not enough to really address the problems.

Here's another indicator. A recent conversation with someone at McAfee revealed that new pieces of deployed malware are being indexed at a rate of about 10 per second -- and those are only the ones detected and being reported! Some of the newer attacks are incredibly sophisticated, defeating two-factor authentication and falsifying bank statements in real time. The criminals are even operating a vast network of fake merchant sites designed to corrupt visitors' machines and steal financial information. Some accounts place the annual losses in the US alone at over $100 billion per year from cyber crime activities -- well over 300 times everything being spent by the US government in R&D to stop it. (Hey, but what's 100 billion dollars, anyhow?) I have heard unpublished reports that some of the criminal gangs involved are spending tens of millions of dollars a year to write new and more effective attacks. Thus, by some estimates, the criminals are vastly outspending the US Government on R&D in this arena, and that doesn't count what other governments are spending to steal classified data and compromise infrastructure. They must be investing wisely, too: how many instances of arrests and takedowns can you recall hearing about recently?

Meanwhile, we are still awaiting the appointment of the National Cyber Cheerleader. For those keeping score, the President announced that the position was critical and he would appoint someone to that position right away. That was on May 29th. Given the delay, one wonders why the National Review was mandated as being completed in a rush 60 day period. As I noted in that earlier posting, an appointment is unlikely to make much of a difference as the position won't have real authority. Even with an appointment, there is disagreement about where the lead for cyber should be, DHS or the military. Neither really seems to take into account that this is at least as much a law enforcement problem as it is one of building better defenses. The lack of agreement means that the tenure of any appointment is likely to be controversial and contentious at worst, and largely ineffectual at best.

I could go on, but it is all rather bleak, especially when viewed through the lens of my 20+ years experience in the field. The facts and trends have been well documented for most of that time, too, so it isn't as if this is a new development. There are some bright points, but unless the problem gets a lot more attention (and resources) than it is getting now, the future is not going to look any better.

So, here are my take-aways for National Cyber Security Awareness:

- the government is more focused on us being "aware" than "secure"

- the criminals are probably outspending the government in R&D

- no one is really in charge of organizing the response, and there isn't agreement about who should

- there aren't enough real experts, and there is little real effort to create more

- too many people think "certification" means "expertise"

- law enforcement in cyber is not a priority

- real education is not a real priority

But hey, don't give up on October! It's also Vegetarian Awareness Month, National Liver Awareness Month, National Chiropractic Month, and Auto Battery Safety Month (among others). Undoubtedly there is something to celebrate without having to wait until Halloween. And that's my contribution for National Positive Attitude Month.