Posts in Secure IT Practices

Page Content

Happy Anniversary—Bang My Head Against A Wall

Over the last month or two I have received several invitations to go speak about cyber security. Perhaps the up-tick in invitations is because of the allegations by Edward Snowden and their implications for cyber security. Or maybe it is because news of my recent awards has caught their attention. It could be it is simply to hear about something other than the (latest) puerile behavior by too many of our representatives in Congress and I'm an alternative chosen at random. Whatever the cause, I am tempted to accept many of these invitations on the theory that if I refuse too many invitations, people will stop asking, and then I wouldn't get to meet as many interesting people.

As I've been thinking about what topics I might speak about, I've been looking back though the archive of talks I've given over the last few decades. It's a reminder of how many things we, as a field, knew about a long time ago but have been ignored by the vendors and authorities. It's also depressing to realize how little impact I, personally, have had on the practice of information security during my career. But, it has also led me to reflect on some anniversaries this year (that happens to us old folk). I'll mention three in particular here, and may use others in some future blogs.

In early November of 1988 the world awoke to news of the first major, large-scale Internet incident. Some self-propagating software had spread around the nascent Internet, causing system crashes, slow-downs, and massive uncertainty. It was really big news. Dubbed the "Internet Worm," it served as an inspiration for many malware authors and vandals, and a wake-up call for security professionals. I recall very well giving talks on the topic for the next few years to many diverse audiences about how we must begin to think about structuring systems to be resistant to such attacks.

Flash forward to today. We don't see the flashy, widespread damage of worm programs any more, such as what Nimda and Code Red caused. Instead, we have more stealthy botnets that infiltrate millions of machines and use them for spam, DDOS, and harassment. The problem has gotten larger and worse, although in a manner that hides some of its magnitude from the casual observer. However, the damage is there; don't try to tell the folks at Saudi Aramaco or Qatar's Rasgas that network malware isn't a concern any more! Worrisomely, experts working with SCADA systems around the world are increasingly warning how vulnerable they might be to similar attacks in the future.

Computer viruses and malware of all sorts first notably appeared "in the wild" in 1982. By 1988 there were about a dozen in circulation. Those of us advocating for more care in design, programming and use of computers were not heeded in the head-long rush to get computing available on every desktop (and more) at the lowest possible cost. Thus, we now have (literally) tens of millions of distinct versions of malware known to security companies, with millions more appearing every year. And unsafe practices are still commonplace -- 25 years after that Internet Worm.

For the second anniversary, consider 10 years ago. The Computing Research Association, with support from the NSF, convened a workshop of experts in security to consider some Grand Challenges in information security. It took a full 3 days, but we came up with four solid Grand Challenges (it is worth reading the full report and (possibly) watching the video):

- Eliminate epidemic-style attacks within 10 years

- Viruses and worms

- SPAM

- Denial of Service attacks (DOS)

- Develop tools and principles that allow construction of large-scale systems for important societal applications that are highly trustworthy despite being attractive targets.

- Within 10 years, quantitative information-systems risk management will be at least as good as quantitative financial risk management.

- For the dynamic, pervasive computing environments of the future, give endusers security they can understand and privacy they can control.

I would argue -- without much opposition from anyone knowledgeable, I daresay -- that we have not made any measurable progress against any of these goals, and have probably lost ground in at least two.

Why is that? Largely economics, and bad understanding of what good security involves. The economics aspect is that no one really cares about security -- enough. If security was important, companies would really invest in it. However, they don't want to part with all the legacy software and systems they have, so instead they keep stumbling forward and hope someone comes up with magic fairy dust they can buy to make everything better.

The government doesn't really care about good security, either. We've seen that the government is allegedly spending quite a bit on intercepting communications and implanting backdoors into systems, which is certainly not making our systems safer. And the DOD has a history of huge investment into information warfare resources, including buying and building weapons based on unpatched, undisclosed vulnerabilities. That's offense, not defense. Funding for education and advanced research is probably two orders of magnitude below what it really should be if there was a national intent to develop a secure infrastructure.

As far as understanding security goes, too many people still think that the ability to patch systems quickly is somehow the approach to security nirvana, and that constructing layers and layers of add-on security measures is the path to enlightenment. I no longer cringe when I hear someone who is adept at crafting system exploits referred to as a "cyber security expert," but so long as that is accepted as what the field is all about there is little hope of real progress. As J.R.R. Tolkien once wrote, "He that breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom." So long as people think that system penetration is a necessary skill for cyber security, we will stay on that wrong path.

And that is a great segue into the last of my three anniversary recognitions. Consider this quote (one of my favorite) from 1973 -- 40 years ago -- from a USAF report, Preliminary Notes on the Design of Secure Military Computer Systems, by a then-young Roger Schell:

…From a practical standpoint the security problem will remain as long as manufacturers remain committed to current system architectures, produced without a firm requirement for security. As long as there is support for ad hoc fixes and security packages for these inadequate designs and as long as the illusory results of penetration teams are accepted as demonstrations of a computer system security, proper security will not be a reality.

That was something we knew 40 years ago. To read it today is to realize that the field of practice hasn't progressed in any appreciable way in three decades, except we are now also stressing the wrong skills in developing the next generation of expertise.

Maybe I'll rethink that whole idea of going to give a talks on security and simply send them each a video loop of me banging my head against a wall.

PS -- happy 10th annual National Cyber Security Awareness Month -- a freebie fourth anniversary! But consider: if cyber security were really important, wouldn't we be aware of that every month? The fact that we need to promote awareness of it is proof it isn't taken seriously. Thanks, DHS!

Now, where can I find I good wall that doesn't already have dents from my forehead....?

A Valuable Resource for Young People (limited time offer)

Over the years, I've gotten to know many people working in security and privacy. Too few have focused on issues relating to children and young adults. Thankfully, one of these people is Linda McCarthy. A security professional with an impressive resume that includes senior positions at Sun Microsystems and Symantec, Linda has had actual "boots-on-the-ground" experience in the practice of information protection.

Linda has written several books on security, including "Intranet Security - Stories from the Trenches," and "IT Security: Risking the Corporation." She also co-authored the recent free, quite popular, Facebook tutorial on security and privacy. I have read these, heard her speak, and worked with her on projects over the years -- Linda is thoughtful, engaging and an effective communicator on the topics of security and privacy. I'm not the only person to think so -- not too long ago she was a recipient of the prestigious Women of Influence award, presented by CSO Magazine and Alta Associates, recognizing her many achievements in security, privacy and risk management.

About a decade ago, based on some personal experiences with young adults close to her, Linda took on the cause of education about how to be safe online. Youngsters seldom have the experience (and the judgement born of experience) to make the best choices about how to protect themselves. Couple that naiveté with the lure of social contact and the lack of highly-visible controls, and toss in a dash of the opportunity to rebel against elders, and a dangerous mix results. Few people, young or old, truly grasp the extent and reach in time and space of the Internet -- postings of pictures and statements never really go away. Marketers, for one, love that depth of data to mine, but it is a nightmare that can haunt the unwary for decades to come.

Long term loss of privacy isn't the only threat, of course. Only last week news broke of yet another tragic suicide caused by cyberbullies; there is a quiet epidemic of this kind of abuse. Also, Miss Teen USA, Cassidy Wolf, spoke a few days ago about being the victim of cyberstalking and sexual extortion. These are not things kids think about when going online -- and neither do their parents. This is the complex milieu that Linda is confronting.

In 2006, Linda began to focus on writing for the younger set and produced "Own Your Space: Keep Yourself and Your Stuff Safe Online," which is a nice introduction that kids seem to appreciate. A few years ago, Linda updated it and under a Creative Commons license it is now available as a free download from Microsoft (among others). I wrote about the release of that update in this blog in 2010.

Earlier this year, Linda released a new book, "Digital Drama: Staying Safe While Being Social Online" (also available en español). This book covers a multitude of issues, including privacy, reputation, online bullying and stalking, avoiding predators, spotting scams, how to manage settings and online persona, and a wealth of other valuable insights for young people -- and therefore it is also of value to their parents, teachers, and an older audience that may not have the expertise but faces many of the same concerns. Linda's book doesn't address all the problems out there -- she doesn't address the really dark side of youth gang culture, for instance -- but this book does admirably cover many of the major issues that face kids who really want to stay out of trouble.

What makes this especially useful is a limited-time offer. In support of National Cyber Security Awareness Month, Microsoft has provided support to allow Linda to offer a free digital download of "Digital Drama" from Amazon.com (the Spanish version, too). Parents, teachers, teens, tweens, kids, and the young at heart can all get that free download from 12am on Tuesday, September 24th until 11:59pm on Friday, September 27 (2013; times are PDT). (If you are reading this blog after that week, you should still check out the book.)

To quote from the "About this book" section of Amazon:

Every day, millions of teens log on and make decisions that can compromise their safety, security, privacy, and future. If you are like most teens, you are already using social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook and have your smartphone super-glued to your hand. You tag your friends in photos, share your location and thoughts with friends, and post jokes online that later may be misunderstood. At the same time, you might not realize how that information can affect your reputation and safety, both online and offline. We’ve all heard the horror stories of stolen identities, cyber stalking, pedophiles on the Internet, and lost job, school, and personal opportunities. All teens need to learn how to protect themselves against malware, social networking scams, and cyberbullies. Learn crucial skills:

- Deal with cyberbullies

- Learn key social networking skills

- Protect your privacy

- Create a positive online reputation

-Protect yourself from phishing and malware scams

Spaf sez, "Check it out."

Just sayin

In the June 17, 2013 online interview with Edward Snowden, there was this exchange:

Question:

Answer:

Encryption works. Properly implemented strong crypto systems are one of the few things that you can rely on. Unfortunately, endpoint security is so terrifically weak that NSA can frequently find ways around it.

I simply thought I'd point out a statement of mine that first appeared in print in 1997 on page 9 of Web Security & Commerce (1st edition, O'Reilly, 1997, S. Garfinkel & G. Spafford):

Secure web servers are the equivalent of heavy armored cars. The problem is, they are being used to transfer rolls of coins and checks written in crayon by people on park benches to merchants doing business in cardboard boxes from beneath highway bridges. Further, the roads are subject to random detours, anyone with a screwdriver can control the traffic lights, and there are no police.

I originally came up with an abbreviated version of this quote during an invited presentation at SuperComputing 95 (December of 1995) in San Diego. The quote at that time was everything up to the "Further...." and was in reference to using encryption, not secure WWW servers.

A great deal of what people are surprised about now should not be a surprise -- some of us have been lecturing about elements of it for decades. I think Cassandra was a cyber security professor....

[Added 9/10: This also reminded me of a post from a couple of years ago. The more things change....]

Some thoughts on “cybersecurity” professionalization and education

[I was recently asked for some thoughts on the issues of professionalization and education of people working in cyber security. I realize I have been asked this many times, I and I keep repeating my answers, to various levels of specificity. So, here is an attempt to capture some of my thoughts so I can redirect future queries here.]

There are several issues relating to the area of personnel in this field that make issues of education and professional definition more complex and difficult to define. The field has changing requirements and increasing needs (largely because industry and government ignored the warnings some of us were sounding many years ago, but that is another story, oft told -- and ignored).

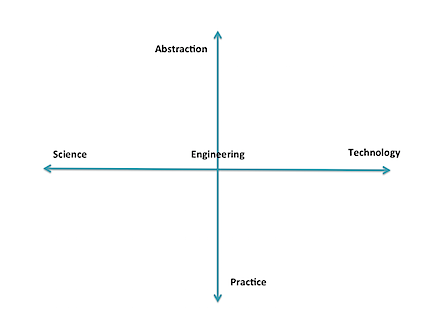

When I talk about educational and personnel needs, I discuss it metaphorically, using two dimensions. Along one axis is the continuum (with an arbitrary directionality) of science, engineering, and technology. Science is the study of fundamental properties and investigation of what is possible -- and the bounds on that possibility. Engineering is the study of design and building new artifacts under constraints. Technology is the study of how to choose from existing artifacts and employ them effectively to solve problems.

The second axis is the range of pure practice to abstraction. This axis is less linear than the other (which is not exactly linear, either), and I don't yet have a good scale for it. However, conceptually I relate it to applying levels of abstraction and anticipation. At its "practice" end are those who actually put in the settings and read the logs of currently-existing artifacts; they do almost no hypothesizing. Moving the other direction we see increasing interaction with abstract thought, people and systems, including operations, law enforcement, management, economics, politics, and eventually, pure theory. At one end, it is "hands-on" with the technology, and at the other is pure interaction with people and abstractions, and perhaps no contact with the technology.

There are also levels of mastery involved for different tasks, such as articulated in Bloom's Taxonomy of learning. Adding that in would provide more complexity than can fit in this blog entry (which is already too long).

The means of acquisition of necessary expertise varies for any position within this field. Many technicians can be effective with simple training, sometimes with at most on-the-job experience. They usually need little or no background beyond everyday practice. Those at the extremes of abstract thought in theory or policy need considerably more background, of the form we generally associate with higher education (although that is not strictly required), often with advanced degrees. And, of course, throughout, people need some innate abilities and motivation for the role they seek; Not everyone has ability, innate or developed, for each task area.

We have need of the full spectrum of these different forms of expertise, with government and industry currently putting an emphasis on the extremes of the quadrant involving technology/practice -- they have problems, now, and want people to populate the "digital ramparts" to defend them. This emphasis applies to those who operate the IDS and firewalls, but also to those who find ways to exploit existing systems (that is an area I believe has been overemphasized by government. Cf. my old blog post and a recent post by Gary McGraw). Many, if not most, of these people can acquire needed skills via training -- such as are acquired on the job, in 1-10 day "minicourses" provided by commercial organizations, and vocational education (e.g, some secondary ed, 2-year degree programs). These kinds of roles are easily designated with testing and course completion certificates.

Note carefully that there is no value statement being made here -- deeply technical roles are fundamental to civilization as we know it. The plumbers, electricians, EMTs, police, mechanics, clerks, and so on are key to our quality of life. The programs that prepare people for those careers are vital, too.

Of course, there are also careers that are directly located in many other places in the abstract plane illustrated above: scientists, software engineers, managers, policy makers, and even bow tie-wearing professors. :-)

One problem comes about when we try to impose sharply-defined categories on all of this, and say that person X has sufficient mastery of the category to perform tasks A, B, and C that are perceived as part of that category. However, those categories are necessarily shifting, not well-defined, and new needs are constantly arising. For instance, we have someone well trained in selecting and operating firewalls and IDS, but suddenly she is confronted with the need to investigate a possible act of nation-state espionage, determine what was done, and how it happened. Or, she is asked to set corporate policy for use of BYOD without knowledge of all the various job functions and people involved. Further deployment of mobile and embedded computing will add further shifts. The skills to do most of these tasks are not easily designated, although a combination of certificates and experience may be useful.

Too many (current) educational programs stress only the technology -- and many others include significant technology training components because of pressure by outside entities -- rather than a full spectrum of education and skills. We have a real shortage of people who have any significant insight into the scope of application of policy, management, law, economics, psychology and the like to cybersecurity, although arguably, those are some of the problems most obvious to those who have the long view. (BTW, that is why CERIAS was founded 15 years ago including faculty in nearly 20 academic departments: "cybersecurity" is not solely a technology issue; this has more recently been recognized by several other universities that are now also treating it holistically.) These other skill areas often require deeper education and repetition of exercises involving abstract thought. It seems that not as many people are naturally capable of mastering these skills. The primary means we use to designate mastery is through postsecondary degrees, although their exact meaning does vary based on the granting institution.

So, consider some the bottom line questions of "professionalization" -- what is, exactly, the profession? What purposes does it serve to delineate one or more niche areas, especially in a domain of knowledge and practice that changes so rapidly? Who should define those areas? Do we require some certification to practice in the field? Given the above, I would contend that too many people have too narrow a view of the domain, and they are seeking some way of ensuring competence only for their narrow application needs. There is therefore a risk that imposing "professional certifications" on this field would both serve to further skew the perception of what is involved, and discourage development of some needed expertise. Defining narrow paths or skill sets for "the profession" might well do the same. Furthermore, much of the body of knowledge is heuristics and "best practice" that has little basis in sound science and engineering. Calling someone in the 1600s a "medical professional" because he knew how to let blood, apply leeches, and hack off limbs with a carpenter's saw using assistants to hold down the unanesthitized patient creates a certain cognitive dissonance; today, calling someone a "cyber security professional" based on knowledge of how to configure Windows, deploy a firewall, and install anti-virus programs should probably be viewed as a similar oddity. We need to evolve to where the deployed base isn't so flawed, and we have some knowledge of what security really is -- evolve from the equivalent of "sawbones" to infectious disease specialists.

We have already seen some of this unfortunate side-effect with the DOD requirements for certifications. Now DOD is about to revisit the requirements, because they have found that many people with certifications don't have the skills they (DOD) think they want. Arguably, people who enter careers and seek (and receive) certification are professionals, at least in a current sense of that word. It is not their fault that the employers don't understand the profession and the nature of the field. Also notable are cases of people with extensive experience and education, who exceed the real needs, but are not eligible for employment because they have not paid for the courses and exams serving as gateways for particular certificates -- and cash cows for their issuing organizations. There are many disconnects in all of this. We also saw skew develop in the academic CAE program.

Here is a short parable that also has implications for this topic.

In the early 1900s, officials with the Bell company (telephones) were very concerned. They told officials and the public that there was a looming personnel crisis. They predicted that, at the then-current rate of growth, by the end of the century everyone in the country would need to be a telephone operator or telephone installer. Clearly, this was impossible.

Fast forward to recent times. Those early predictions were correct. Everyone was an installer -- each could buy a phone at the corner store, and plug it into a jack in the wall at home. Or, simpler yet, they could buy cellphones that were already on. And everyone was an operator -- instead of using plugboards and directory assistance, they would use an online service to get a phone number and enter it in the keypad (or speed dial from memory). What happened? Focused research, technology evolution, investment in infrastructure, economics, policy, and psychology (among others) interacted to "shift the paradigm" to one that no longer had the looming personnel problems.

If we devoted more resources and attention to the broadly focused issues of information protection (not "cyber" -- can we put that term to rest?), we might well obviate many of the problems that now require legions of technicians. Why do we have firewalls and IDS? In large part, because the underlying software and hardware was not designed for use in an open environment, and its development is terribly buggy and poorly configured. The languages, systems, protocols, and personnel involved in the current infrastructure all need rethinking and reengineering. But so long as the powers-that-be emphasize retaining (and expanding) legacy artifacts and compatibility based on up-front expense instead of overall quality, and in training yet more people to be the "cyber operators" defending those poor choices, we are not going to make the advances necessary to move beyond them (and, to repeat, many of us have been warning about that for decades). And we are never going to have enough "professionals" to keep them safe. We are focusing on the short term and will lose the overall struggle; we need to evolve our way out of the problems, not meet them with an ever-growing band of mercenaries.

The bottom line? We should be very cautious in defining what a "professional" is in this field so that we don't institutionalize limitations and bad practices. And we should do more to broaden the scope of education for those who work in those "professions" to ensure that their focus -- and skills -- are not so limited as to miss important features that should be part of what they do. As one glaring example, think "privacy" -- how many of the "professionals" working in the field have a good grounding and concern about preserving privacy (and other civil rights) in what they do? Where is privacy even mentioned in "cybersecurity"? What else are they missing?

[If this isn't enough of my musings on education, you can read two of my ideas in a white paper I wrote in 2010. Unfortunately, although many in policy circles say they like the ideas, no one has shown any signs of acting as a champion for either.]

[3/2/2013] While at the RSA Conference, I was interviewed by the Information Security Media Group on the topic of cyber workforce. The video is available online.

On Student Projects, Phoenix, and Improving Your IT Operations

[If you want to skip my recollection and jump right to the announcement that is the reason for this post, go here.]

Back in about 1990 I was approached by an eager undergrad who had recently come to Purdue University. A mutual acquaintance (hi, Rob!) had recommended that the student connect with me for a project. We chatted for a bit and at first it wasn't clear exactly what he might be able to do. He had some experience coding, and was working in the campus computing center, but had no background in the more advanced topics in computing (yet).

Well, it just so happened that a few months earlier, my honeypot Sun workstation had recorded a very sophisticated (for the time) attack, which resulted in an altered shared library with a back door in place. The attack was stealthy, and the new library had the same dates, size and simple hash value as the original. (The attack was part of a larger series of attacks, and eventually documented in "@Large: The Strange Case of the World's Biggest Internet Invasion" (David H. Freedman, Charles C. Mann .)

I had recently been studying message digest functions and had a hunch that they might provide better protection for systems than a simple ls -1 | diff - old comparison. However, I wanted to get some operational sense about the potential for collision in the digests. So, I tasked the student with devising some tests to run many files through a version of the digest to see if there were any collisions. He wrote a program to generate some random files, and all seemed okay based on that. I suggested he look for a different collection -- something larger. He took my advice a little too much to heart. It seems he had a part time job running backup jobs on the main shared instructional computers at the campus computing center. He decided to run the program over the entire file system to look for duplicates. Which he did one night after backups were complete.

The next day (as I recall) he reported to me that there were no unexpected collisions over many hundreds of thousands of files. That was a good result!

The bad result was that running his program over the file system had resulted in a change of the access time of every file on the system, so the backups the next evening vastly exceeded the existing tape archive and all the spares! This led directly to the student having a (pointed) conversation with the director of the center, and thereafter, unemployment. I couldn't leave him in that position mid-semester so I found a little money and hired him as an assistant. I them put him to work coding up my idea, about how to use the message digests to detect changes and intrusions into a computing system. Over the next year, he would code up my design, and we would do repeated, modified "cleanroom" tests of his software. Only when they all passed, did we release the first version of Tripwire.

That is how I met Gene Kim .

Gene went on to grad school elsewhere, then a start-up, and finally got the idea to start the commercial version of Tripwire with Wyatt Starnes; Gene served as CTO, Wyatt as CEO. Their subsequent hard work, and that of hundreds of others who have worked at the company over the years, resulted in great success: the software has become one of the most widely used change detection & IDS systems in history, as well as inspiring many other products.

Gene became more active in the security scene, and was especially intrigued with issues of configuration management, compliance, and overall system visibility, and with their connections to security and correctness. Over the years he spoken with thousands of customers and experts in the industry, and heard both best-practice and horror stories involving integrity management, version control, and security. This led to projects, workshops, panel sessions, and eventually to his lead authorship of "Visible Ops Security: Achieving Common Security and IT Operations Objectives in 4 Practical Steps" (Gene Kim, Paul Love, George Spafford) , and some other, related works.

His passion for the topic only grew. He was involved in standards organizations, won several awards for his work, and even helped get the B-sides conferences into a going concern. A few years ago, he left his position at Tripwire to begin work on a book to better convey the principles he knew could make a huge difference in how IT is managed in organizations big and small.

I read an early draft of that book a little over a year ago (late 2011), It was a bit rough -- Gene is bright and enthusiastic, but was not quite writing to the level of J.K. Rowling or Stephen King. Still, it was clear that he had the framework of a reasonable narrative to present major points about good, bad, and excellent ways to manage IT operations, and how to transform them for the better. He then obtained input from a number of people (I think he ignored mine), added some co-authors, and performed a major rewrite of the book. The result is a much more readable and enjoyable story -- a cross between a case study and a detective novel, with a dash of H. P. Lovecraft and DevOps thrown in.

The official launch date of the book, "The Phoenix Project: A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win" (Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, George Spafford), is Tuesday, January 15, but you can preorder it before then on (at least) Amazon.

The book is worth reading if you have a stake in operations at a business using IT. If you are a C-level executive, you should most definitely take time to read the book. Consultants, auditors, designers, educators...there are some concepts in there for everyone.

But you don't have to take only my word for it -- see the effusive praise of tech luminaries who have read the book .

So, Spaf sez, get a copy and see how you can transform your enterprise for the better.

(Oh, and I have never met the George Spafford who is a coauthor of the book. We are undoubtedly distant cousins, especially given how uncommon the name is. That Gene would work with two different Spaffords over the years is one of those cosmic quirks Vonnegut might write about. But Gene isn't Vonnegut, either. :-)

So, as a postscript.... I've obviously known Gene for over 20 years, and am very fond of him, as well as happy for his continuing success. However, I have had a long history of kidding him, which he has taken with incredible good nature. I am sure he's saving it all up to get me some day....

When Gene and his publicist asked if I could provide some quotes to use for his book, I wrote the first of the following. For some reason, this never made it onto the WWW site . So, they asked me again, and I wrote the second of the following -- which they also did not use.

So, not to let a good review (or two) go to waste, I have included them here for you. If nothing else, it should convince others not to ask me for a book review.

But, despite the snark (who, me?) of these gag reviews, I definitely suggest you get a copy of the book and think about the ideas expressed therein. Gene and his coauthors have really produced a valuable, readable work that will inform -- and maybe scare -- anyone involved with organizational IT.

Take 1:

Based on my long experience in academia, I can say with conviction that this is truly a book, composed of an impressive collection of words, some of which exist in human languages. Although arranged in a largely random order, there are a few sentences that appear to have both verbs and nouns. I advise that you immediately buy several copies and send them to people -- especially people you don't like -- and know that your purchase is helping keep some out of the hands of the unwary and potentially innocent. Under no circumstances, however, should you read the book before driving or operating heavy machinery. This work should convince you that Gene Kim is a visionary (assuming that your definition of "vision" includes "drug-induced hallucination").

Take 2:

I picked up this new book -- The Phoenix Project , by Gene Kim, et al. -- and could not put it down. You probably hear people say that about books in which they are engrossed. But I mean this literally: I happened to be reading it on my Kindle while repairing some holiday ornaments with superglue. You might say that the book stuck with me for a while.

There are people who will tell you that Gene Kim is a great author and raconteur. Those people, of course, are either trapped in Mr. Kim's employ or they drink heavily. Actually, one of those conditions invariably leads to the other, along with uncontrollable weeping, and the anguished rending of garments. Notwithstanding that, Mr. Kim's latest assault on les belles-lettres does indeed prompt this reviewer to some praise: I have not had to charge my health spending account for a zolpidem refill since I received the advance copy of the book! (Although it may be why I now need risperidone.)

I must warn you, gentle reader, that despite my steadfast sufferance in reading, I never encountered any mention of an actual Phoenix. I skipped ahead to the end, and there was no mention there, either. Neither did I notice any discussion of a massive conflagration nor of Arizona, either of which might have supported the reference to Phoenix . This is perhaps not so puzzling when one recollects that Mr. Kim's train of thought often careens off the rails with any random, transient manifestation corresponding to the meme "Ooh, a squirrel!" Rather, this work is more emblematic of a bus of thought, although it is the short bus, at that.

Despite my personal trauma, I must declare the book as a fine yarn: not because it is unduly tangled (it is), but because my kitten batted it about for hours with the evident joy usually limited to a skein of fine yarn. I have found over time it is wise not to argue with cats or women. Therefore, appease your inner kitten and purchase a copy of the book. Gene Kim's court-appointed guardians will thank you. Probably.

(Congratulations Gene, Kevin and George!)

Is encrypting my email any good at defeating the NSA survelielance? Id my data protected by standard encryption?