The Center for Education and Research in Information Assurance and Security (CERIAS)

The Center for Education and Research inInformation Assurance and Security (CERIAS)

This is a follow-up to my last post here, about the "cybersecurity profession" and education. I was moderating one of the panels at the most recent CERIAS Symposium, and a related topic came up.

Let's start with some short mental exercises. Limber up your cerebellum. Stretch out and touch your cognitive centers a few times. Ready?

There's another barn on fire! Quick, get a bucket brigade going -- we need to put the fire out before everything burns. Again. It is getting so tiring watching all our stuff burn while we're trying to run a farm here. Too bad we can only afford the barns constructed of fatwood. But no time to think of that -- a barn's burning again! 3rd time this week!

Hey, you people over there tinkering with designs for sprinkler systems and concrete barns -- cut it out! We can't spare you to do that -- too many barns are burning! And you, stop babbling about investigating and arresting arsonists -- we don't have time or money for that: didn't you hear me? Another barn is burning!

Now, hurry up. We're going to have a contest to find who can pass this pail of water the quickest. Yes, it is a small, leaky pail, but we have a lot of them, so that is what we're going to use in the contest. The winners get to be closest to the flames and have a name tag that says "fire prevention specialist." No, we can't afford larger buckets. And no, you can't go get a hose -- we need you in the line. Damnit! The barn's burning!

Sounds really stupid, doesn't it? Whoever is in charge isn't doing anything to address the underlying problem of poor barn construction. It doesn't really match the notion of what a fire prevention specialist might really do. And it certainly doesn't provide deep career preparation for any of those contestants... it may even condemn them to a future of menial bucket passing because we're putting them on the line with no training or qualification beyond being able to pass a bucket.

Let's try another one.

Imagine that every car and automobile in the country has been poorly designed. They almost all leak coolant and burn oil. They're trivial to steal. They are mostly cheap junkers, all built on the same frame with the same engines, accessories, and tires -- even the ones sold to the police and military (actually, they're the same cars, but with different paint). The big automakers are rolling out new models every year that they advertise as being more efficient and reliable, but that is simply hype to get you to buy a new car because the new features also regularly break down. There are a few good models available, but they are quite a bit more expensive; those more expensive ones often (but not always) break down less, are more difficult to steal, and get far better mileage. Their vendors also don't have a yearly model update, and many consumers aren't interested in them because those cars don't take the common size of tire or fuzzy dice for the mirror.

The auto companies have been building this way for decades. They sell their products around the world, and they're a major economic force. Everyone needs a car, and they shell out money for new ones on a regular basis. People grumble about the poor quality and the breakdowns, but other than periodic service bulletins, there are few changes from year to year. Many older, more decrepit cars are on the road because too many people (and companies) cannot afford to buy new ones that they know aren't much better than the old ones. Many people argue -- vociferously -- against any attempt to put safety regulations on the car companies because it might hurt such an important market segment.

A huge commercial enterprise has sprung up around fixing cars and adding on replacement parts that are supposedly more reliable. People pour huge amounts of money into this market because they depend on the cars for work, play, safety, shopping, and many other things. However, there are so many cars, and so many update bulletins and add-ons, there simply aren't enough trained mechanics to keep up -- especially because many of the add-ons don't work, or require continual adjustment.

What to do? Aha! We'll encourage young people in high school and maybe college to become "automotive specialists." We'll publish all sorts of articles with doom and gloom as a result of the shortage of people going into auto repair. We especially need lots more military mechanics.

So...we'll have competitions! We'll offer prizes to the individuals (or teams) that are able to change the oil of last year's model the most quickly, or who can most efficiently hotwire a pickup truck, take it to the garage, change the tires, and return it. The government will support these competitions. They'll get lots of press. Some major professional organizations and even universities will promote these. Of course we'll hire lots of mechanics that way! (Women aren't interested in these kinds of competition? We won't worry about that now. People who are poor with wrenches won't compete? No problem -- we'll fill in with the rest.)

Meanwhile, the government and major companies aren't really doing anything to fix the actual engineering of the automobiles. There are a few comprehensive engineering programs at universities around the country, but minimal focus and resources are applied there, and little is said about applying their knowledge to really fixing transportation. The government, especially the military, simply wants more mechanics and cheaper cars -- overall safety and reliability aren't a major concern.

Pretty stupid, huh? But there does seem to be a trend to these exercises.

Let's try one more.

We have a large population that needs to be fed. They've grown accustomed to cheap, fast-food. Everyone eats at the drive-thru, where they get a burger or compressed chicken by-product or mystery-meat taco. It's filling, and it keeps them going for the day. It also leads to obesity, hypertension, cardiac problems, diabetes, and more. However, no one really blames the fast-food chains, because they are simply providing what people want.

It isn't exactly what people should have, and is it really what everyone wants? No, there are better restaurants with healthy food, but that food is more expensive and many people would go hungry if they had to eat at those places given the current economic model. Of course, if they didn't need to spend so much on medicine and hospital stays, a healthier diet is actually cheaper. Also, those better places aren't easy to find -- small (or no) advertising budgets, for instance.

The government has contracted with the chains for food, and even serves it at every government office and on every military base. The chains thus have a fair amount of political clout so that every time someone raises the issue about how unhealthy the food is, they get muffled by the arguments "But it would be too expensive to eat healthy" and "Most people don't like that other food and can't even find it!"

We have a crisis because the demand for the fast-food is so great that there aren't enough fry cooks. So, the heads of major military organizations and government agencies observe we are facing a crisis because, without enough fry cooks, our troops will be overwhelmed by better fed people from China. Government officials and industry people agree because they can't imagine any better diet (or are so enamored of fried potatoes that they don't want anything else).

How do they address the crisis? By mounting advertising campaigns to encourage young people to enter the exciting world of "cuisine awareness." We make it seem glamorous. Private organizations offer certifications in "soda making" and "ketchup bottle maintenance" that are awarded after 3-day seminars. DOD requires anyone working in food service to have one of these certificates -- and that's basically all. We see educational institutes and small colleges offering special programs in "salad bar maintenance." The generals and admirals keep showing up at meetings proclaiming how important it is that we get more burger-flippers in place before we have a "patty melt Pearl Harbor."

The government launches a program to certify schools as centers of "Cuisine Awareness Exellence" if they can prove they have at least 5 cookbooks in the library, a crockpot, and two faculty who have boiled water. Soon, there are hundreds of places designated with this CAE, from taco trucks and hot dog stands to cordon bleu centers -- but lots are only hot dog stands. None of them are given any recipes, cooks, or financial support, of course -- simply designating them is enough, right?

When all of that isn't seen to be enough, the powers-that-be offer up contests that encourage kids to show up and cook. Those who are able to most quickly defrost a compressed cake of Soylent Red, cook it, stick it in a bun, and serve it up in a bag with fries is declared the winner and given a job behind someone's grill. Actually, each registered contestant gets a jaunty paper cap and offer of an immediate job cooking for the military (assuming they are U.S. citizens; after all, we know what those furriners eat sure isn't food!) And gosh, how could they aspire to be anything BUT a fry cook for the next 40 years -- no need to worry about any real education before they take the jobs.

Meanwhile, those studying dietetics, preventative health care, sustainable agriculture, haute cuisine, or other related topics are largely ignored -- not to mention the practicing experts in these fields. The people and places of study for those domains are ignored by the officials, and many of the potential employers in those areas are actually going out of business because of lack of public interest and support. The advice of the experts on how to improve diet is ignored. Find that disconcerting? Here -- have a deep-fried cherry pie and a chocolate ersatz-dairy item drink to make you feel better.

Did you sense a set of common threads (assuming you didn't blow out your cortex in the exercise)?

First, in every case, a mix of short-sighted and ultimately stupid solutions are being undertaken. In each, there are large-scale efforts to address pressing problems that largely ignore fundamental, systemic weaknesses.

Second, there are a set of efforts putatively being made to increase the population of experts, but only with those who know how to address a current, limited problem set. Fancy titles, certificates, and seminars are used to promote these technicians. Meanwhile, longer-term expertise and solutions are being ignored because of the perceived urgency of the immediate problems and a lack of understanding of cost and risk.

Third, longer-term disaster is clearly coming in each case because of secondary problems and growth of the current threats.

Why did this come up with my post and panel on cybersecurity? I would hope that would be obvious, but if not, let me suggest you go back to read my prior post, then read the above examples, again. Then, consider:

One of the most egregious aspects is this last item -- the increasing use of competitions as a way of drawing people to the field. Competitions, by their very nature, stress learned behavior to react to current problems that are likely small deviations from past issues. They do not require extensive grounding in multiple fields. Competitions require rapid response instead of careful design and deep thought -- if anything, they discourage people who exhibit slow, considerate thinking -- discourage them from the contests, and possibly from considering the field itself. If what is being promoted are competitions for the fastest hack on a WIntel platform, how is that going to encourage deep thinkers interested in architecture, algorithms, operating systems, cryptology, or more?

Competitions encourage the mindset of hacking and patching, not of strong design. Competitions encourage the mindset of quick recovery over the gestalt of design-operate-observe-investigate-redesign. Because of the high-profile, high-pressure nature of competitions, they are likely to discourage the philosophical and the careful thinkers. Speed is emphasized over comprehensive and robust approaches. Competitions are also likely to disproportionately discourage women, the shy, and those with expertise in non-mainstream systems. In short, competitions select for a narrow set of skills and proclivities -- and may discourage many of the people we most need in the field to address the underlying problems.

So, the next time you hear some official talk about the need for "cyber warriors" or promoting some new "capture the flag" competition, ask yourself if you want to live in a world where the barns are always catching fire, the cars are always breaking down, nearly everyone eats fast food, and the major focus of "authorities" is attracting more young people to minimally skilled positions that perpetuate that situation...until everything falls apart. The next time you hear about some large government grant that happens to be within 100 miles of the granting agency's headquarters or corporate support for a program of which the CEO is an alumnus but there is no history of excellence in the field, ask yourself why their support is skewed towards building more hot dog stands.

Those of us here at CERIAS, and some of our colleagues with strategic views elsewhere, remind you that expertise is a pursuit and a process, not a competition or a 3-day class, and some of us take it seriously. We wish you would, too.

Your brain may now return to being a couch potato. :-)

[I was recently asked for some thoughts on the issues of professionalization and education of people working in cyber security. I realize I have been asked this many times, I and I keep repeating my answers, to various levels of specificity. So, here is an attempt to capture some of my thoughts so I can redirect future queries here.]

There are several issues relating to the area of personnel in this field that make issues of education and professional definition more complex and difficult to define. The field has changing requirements and increasing needs (largely because industry and government ignored the warnings some of us were sounding many years ago, but that is another story, oft told -- and ignored).

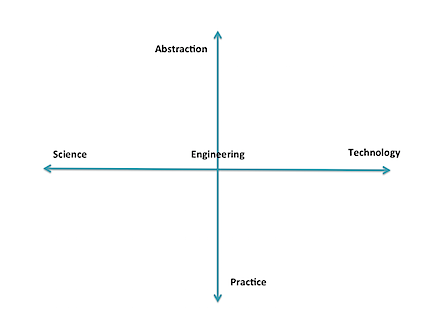

When I talk about educational and personnel needs, I discuss it metaphorically, using two dimensions. Along one axis is the continuum (with an arbitrary directionality) of science, engineering, and technology. Science is the study of fundamental properties and investigation of what is possible -- and the bounds on that possibility. Engineering is the study of design and building new artifacts under constraints. Technology is the study of how to choose from existing artifacts and employ them effectively to solve problems.

The second axis is the range of pure practice to abstraction. This axis is less linear than the other (which is not exactly linear, either), and I don't yet have a good scale for it. However, conceptually I relate it to applying levels of abstraction and anticipation. At its "practice" end are those who actually put in the settings and read the logs of currently-existing artifacts; they do almost no hypothesizing. Moving the other direction we see increasing interaction with abstract thought, people and systems, including operations, law enforcement, management, economics, politics, and eventually, pure theory. At one end, it is "hands-on" with the technology, and at the other is pure interaction with people and abstractions, and perhaps no contact with the technology.

There are also levels of mastery involved for different tasks, such as articulated in Bloom's Taxonomy of learning. Adding that in would provide more complexity than can fit in this blog entry (which is already too long).

The means of acquisition of necessary expertise varies for any position within this field. Many technicians can be effective with simple training, sometimes with at most on-the-job experience. They usually need little or no background beyond everyday practice. Those at the extremes of abstract thought in theory or policy need considerably more background, of the form we generally associate with higher education (although that is not strictly required), often with advanced degrees. And, of course, throughout, people need some innate abilities and motivation for the role they seek; Not everyone has ability, innate or developed, for each task area.

We have need of the full spectrum of these different forms of expertise, with government and industry currently putting an emphasis on the extremes of the quadrant involving technology/practice -- they have problems, now, and want people to populate the "digital ramparts" to defend them. This emphasis applies to those who operate the IDS and firewalls, but also to those who find ways to exploit existing systems (that is an area I believe has been overemphasized by government. Cf. my old blog post and a recent post by Gary McGraw). Many, if not most, of these people can acquire needed skills via training -- such as are acquired on the job, in 1-10 day "minicourses" provided by commercial organizations, and vocational education (e.g, some secondary ed, 2-year degree programs). These kinds of roles are easily designated with testing and course completion certificates.

Note carefully that there is no value statement being made here -- deeply technical roles are fundamental to civilization as we know it. The plumbers, electricians, EMTs, police, mechanics, clerks, and so on are key to our quality of life. The programs that prepare people for those careers are vital, too.

Of course, there are also careers that are directly located in many other places in the abstract plane illustrated above: scientists, software engineers, managers, policy makers, and even bow tie-wearing professors. :-)

One problem comes about when we try to impose sharply-defined categories on all of this, and say that person X has sufficient mastery of the category to perform tasks A, B, and C that are perceived as part of that category. However, those categories are necessarily shifting, not well-defined, and new needs are constantly arising. For instance, we have someone well trained in selecting and operating firewalls and IDS, but suddenly she is confronted with the need to investigate a possible act of nation-state espionage, determine what was done, and how it happened. Or, she is asked to set corporate policy for use of BYOD without knowledge of all the various job functions and people involved. Further deployment of mobile and embedded computing will add further shifts. The skills to do most of these tasks are not easily designated, although a combination of certificates and experience may be useful.

Too many (current) educational programs stress only the technology -- and many others include significant technology training components because of pressure by outside entities -- rather than a full spectrum of education and skills. We have a real shortage of people who have any significant insight into the scope of application of policy, management, law, economics, psychology and the like to cybersecurity, although arguably, those are some of the problems most obvious to those who have the long view. (BTW, that is why CERIAS was founded 15 years ago including faculty in nearly 20 academic departments: "cybersecurity" is not solely a technology issue; this has more recently been recognized by several other universities that are now also treating it holistically.) These other skill areas often require deeper education and repetition of exercises involving abstract thought. It seems that not as many people are naturally capable of mastering these skills. The primary means we use to designate mastery is through postsecondary degrees, although their exact meaning does vary based on the granting institution.

So, consider some the bottom line questions of "professionalization" -- what is, exactly, the profession? What purposes does it serve to delineate one or more niche areas, especially in a domain of knowledge and practice that changes so rapidly? Who should define those areas? Do we require some certification to practice in the field? Given the above, I would contend that too many people have too narrow a view of the domain, and they are seeking some way of ensuring competence only for their narrow application needs. There is therefore a risk that imposing "professional certifications" on this field would both serve to further skew the perception of what is involved, and discourage development of some needed expertise. Defining narrow paths or skill sets for "the profession" might well do the same. Furthermore, much of the body of knowledge is heuristics and "best practice" that has little basis in sound science and engineering. Calling someone in the 1600s a "medical professional" because he knew how to let blood, apply leeches, and hack off limbs with a carpenter's saw using assistants to hold down the unanesthitized patient creates a certain cognitive dissonance; today, calling someone a "cyber security professional" based on knowledge of how to configure Windows, deploy a firewall, and install anti-virus programs should probably be viewed as a similar oddity. We need to evolve to where the deployed base isn't so flawed, and we have some knowledge of what security really is -- evolve from the equivalent of "sawbones" to infectious disease specialists.

We have already seen some of this unfortunate side-effect with the DOD requirements for certifications. Now DOD is about to revisit the requirements, because they have found that many people with certifications don't have the skills they (DOD) think they want. Arguably, people who enter careers and seek (and receive) certification are professionals, at least in a current sense of that word. It is not their fault that the employers don't understand the profession and the nature of the field. Also notable are cases of people with extensive experience and education, who exceed the real needs, but are not eligible for employment because they have not paid for the courses and exams serving as gateways for particular certificates -- and cash cows for their issuing organizations. There are many disconnects in all of this. We also saw skew develop in the academic CAE program.

Here is a short parable that also has implications for this topic.

In the early 1900s, officials with the Bell company (telephones) were very concerned. They told officials and the public that there was a looming personnel crisis. They predicted that, at the then-current rate of growth, by the end of the century everyone in the country would need to be a telephone operator or telephone installer. Clearly, this was impossible.

Fast forward to recent times. Those early predictions were correct. Everyone was an installer -- each could buy a phone at the corner store, and plug it into a jack in the wall at home. Or, simpler yet, they could buy cellphones that were already on. And everyone was an operator -- instead of using plugboards and directory assistance, they would use an online service to get a phone number and enter it in the keypad (or speed dial from memory). What happened? Focused research, technology evolution, investment in infrastructure, economics, policy, and psychology (among others) interacted to "shift the paradigm" to one that no longer had the looming personnel problems.

If we devoted more resources and attention to the broadly focused issues of information protection (not "cyber" -- can we put that term to rest?), we might well obviate many of the problems that now require legions of technicians. Why do we have firewalls and IDS? In large part, because the underlying software and hardware was not designed for use in an open environment, and its development is terribly buggy and poorly configured. The languages, systems, protocols, and personnel involved in the current infrastructure all need rethinking and reengineering. But so long as the powers-that-be emphasize retaining (and expanding) legacy artifacts and compatibility based on up-front expense instead of overall quality, and in training yet more people to be the "cyber operators" defending those poor choices, we are not going to make the advances necessary to move beyond them (and, to repeat, many of us have been warning about that for decades). And we are never going to have enough "professionals" to keep them safe. We are focusing on the short term and will lose the overall struggle; we need to evolve our way out of the problems, not meet them with an ever-growing band of mercenaries.

The bottom line? We should be very cautious in defining what a "professional" is in this field so that we don't institutionalize limitations and bad practices. And we should do more to broaden the scope of education for those who work in those "professions" to ensure that their focus -- and skills -- are not so limited as to miss important features that should be part of what they do. As one glaring example, think "privacy" -- how many of the "professionals" working in the field have a good grounding and concern about preserving privacy (and other civil rights) in what they do? Where is privacy even mentioned in "cybersecurity"? What else are they missing?

[If this isn't enough of my musings on education, you can read two of my ideas in a white paper I wrote in 2010. Unfortunately, although many in policy circles say they like the ideas, no one has shown any signs of acting as a champion for either.]

[3/2/2013] While at the RSA Conference, I was interviewed by the Information Security Media Group on the topic of cyber workforce. The video is available online.

[If you want to skip my recollection and jump right to the announcement that is the reason for this post, go here.]

Back in about 1990 I was approached by an eager undergrad who had recently come to Purdue University. A mutual acquaintance (hi, Rob!) had recommended that the student connect with me for a project. We chatted for a bit and at first it wasn't clear exactly what he might be able to do. He had some experience coding, and was working in the campus computing center, but had no background in the more advanced topics in computing (yet).

Well, it just so happened that a few months earlier, my honeypot Sun workstation had recorded a very sophisticated (for the time) attack, which resulted in an altered shared library with a back door in place. The attack was stealthy, and the new library had the same dates, size and simple hash value as the original. (The attack was part of a larger series of attacks, and eventually documented in "@Large: The Strange Case of the World's Biggest Internet Invasion" (David H. Freedman, Charles C. Mann .)

I had recently been studying message digest functions and had a hunch that they might provide better protection for systems than a simple ls -1 | diff - old comparison. However, I wanted to get some operational sense about the potential for collision in the digests. So, I tasked the student with devising some tests to run many files through a version of the digest to see if there were any collisions. He wrote a program to generate some random files, and all seemed okay based on that. I suggested he look for a different collection -- something larger. He took my advice a little too much to heart. It seems he had a part time job running backup jobs on the main shared instructional computers at the campus computing center. He decided to run the program over the entire file system to look for duplicates. Which he did one night after backups were complete.

The next day (as I recall) he reported to me that there were no unexpected collisions over many hundreds of thousands of files. That was a good result!

The bad result was that running his program over the file system had resulted in a change of the access time of every file on the system, so the backups the next evening vastly exceeded the existing tape archive and all the spares! This led directly to the student having a (pointed) conversation with the director of the center, and thereafter, unemployment. I couldn't leave him in that position mid-semester so I found a little money and hired him as an assistant. I them put him to work coding up my idea, about how to use the message digests to detect changes and intrusions into a computing system. Over the next year, he would code up my design, and we would do repeated, modified "cleanroom" tests of his software. Only when they all passed, did we release the first version of Tripwire.

That is how I met Gene Kim .

Gene went on to grad school elsewhere, then a start-up, and finally got the idea to start the commercial version of Tripwire with Wyatt Starnes; Gene served as CTO, Wyatt as CEO. Their subsequent hard work, and that of hundreds of others who have worked at the company over the years, resulted in great success: the software has become one of the most widely used change detection & IDS systems in history, as well as inspiring many other products.

Gene became more active in the security scene, and was especially intrigued with issues of configuration management, compliance, and overall system visibility, and with their connections to security and correctness. Over the years he spoken with thousands of customers and experts in the industry, and heard both best-practice and horror stories involving integrity management, version control, and security. This led to projects, workshops, panel sessions, and eventually to his lead authorship of "Visible Ops Security: Achieving Common Security and IT Operations Objectives in 4 Practical Steps" (Gene Kim, Paul Love, George Spafford) , and some other, related works.

His passion for the topic only grew. He was involved in standards organizations, won several awards for his work, and even helped get the B-sides conferences into a going concern. A few years ago, he left his position at Tripwire to begin work on a book to better convey the principles he knew could make a huge difference in how IT is managed in organizations big and small.

I read an early draft of that book a little over a year ago (late 2011), It was a bit rough -- Gene is bright and enthusiastic, but was not quite writing to the level of J.K. Rowling or Stephen King. Still, it was clear that he had the framework of a reasonable narrative to present major points about good, bad, and excellent ways to manage IT operations, and how to transform them for the better. He then obtained input from a number of people (I think he ignored mine), added some co-authors, and performed a major rewrite of the book. The result is a much more readable and enjoyable story -- a cross between a case study and a detective novel, with a dash of H. P. Lovecraft and DevOps thrown in.

The official launch date of the book, "The Phoenix Project: A Novel About IT, DevOps, and Helping Your Business Win" (Gene Kim, Kevin Behr, George Spafford), is Tuesday, January 15, but you can preorder it before then on (at least) Amazon.

The book is worth reading if you have a stake in operations at a business using IT. If you are a C-level executive, you should most definitely take time to read the book. Consultants, auditors, designers, educators...there are some concepts in there for everyone.

But you don't have to take only my word for it -- see the effusive praise of tech luminaries who have read the book .

So, Spaf sez, get a copy and see how you can transform your enterprise for the better.

(Oh, and I have never met the George Spafford who is a coauthor of the book. We are undoubtedly distant cousins, especially given how uncommon the name is. That Gene would work with two different Spaffords over the years is one of those cosmic quirks Vonnegut might write about. But Gene isn't Vonnegut, either. :-)

So, as a postscript.... I've obviously known Gene for over 20 years, and am very fond of him, as well as happy for his continuing success. However, I have had a long history of kidding him, which he has taken with incredible good nature. I am sure he's saving it all up to get me some day....

When Gene and his publicist asked if I could provide some quotes to use for his book, I wrote the first of the following. For some reason, this never made it onto the WWW site . So, they asked me again, and I wrote the second of the following -- which they also did not use.

So, not to let a good review (or two) go to waste, I have included them here for you. If nothing else, it should convince others not to ask me for a book review.

But, despite the snark (who, me?) of these gag reviews, I definitely suggest you get a copy of the book and think about the ideas expressed therein. Gene and his coauthors have really produced a valuable, readable work that will inform -- and maybe scare -- anyone involved with organizational IT.

Based on my long experience in academia, I can say with conviction that this is truly a book, composed of an impressive collection of words, some of which exist in human languages. Although arranged in a largely random order, there are a few sentences that appear to have both verbs and nouns. I advise that you immediately buy several copies and send them to people -- especially people you don't like -- and know that your purchase is helping keep some out of the hands of the unwary and potentially innocent. Under no circumstances, however, should you read the book before driving or operating heavy machinery. This work should convince you that Gene Kim is a visionary (assuming that your definition of "vision" includes "drug-induced hallucination").

I picked up this new book -- The Phoenix Project , by Gene Kim, et al. -- and could not put it down. You probably hear people say that about books in which they are engrossed. But I mean this literally: I happened to be reading it on my Kindle while repairing some holiday ornaments with superglue. You might say that the book stuck with me for a while.

There are people who will tell you that Gene Kim is a great author and raconteur. Those people, of course, are either trapped in Mr. Kim's employ or they drink heavily. Actually, one of those conditions invariably leads to the other, along with uncontrollable weeping, and the anguished rending of garments. Notwithstanding that, Mr. Kim's latest assault on les belles-lettres does indeed prompt this reviewer to some praise: I have not had to charge my health spending account for a zolpidem refill since I received the advance copy of the book! (Although it may be why I now need risperidone.)

I must warn you, gentle reader, that despite my steadfast sufferance in reading, I never encountered any mention of an actual Phoenix. I skipped ahead to the end, and there was no mention there, either. Neither did I notice any discussion of a massive conflagration nor of Arizona, either of which might have supported the reference to Phoenix . This is perhaps not so puzzling when one recollects that Mr. Kim's train of thought often careens off the rails with any random, transient manifestation corresponding to the meme "Ooh, a squirrel!" Rather, this work is more emblematic of a bus of thought, although it is the short bus, at that.

Despite my personal trauma, I must declare the book as a fine yarn: not because it is unduly tangled (it is), but because my kitten batted it about for hours with the evident joy usually limited to a skein of fine yarn. I have found over time it is wise not to argue with cats or women. Therefore, appease your inner kitten and purchase a copy of the book. Gene Kim's court-appointed guardians will thank you. Probably.

(Congratulations Gene, Kevin and George!)

| Site | Minimum Characters | Reuse? | Trivial? | All lower-case? | Expiration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| 8 | No | No | Yes | No | |

| 6 | Yes | No | Yes | No |